Medical Disorders in Pregnancy

Sickle Cell Anemia

Definition and Pathophysiology

Sickle cell anemia is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by abnormal hemoglobin S (HbS). The mutation leads to the destruction of red blood cells.

Prepregnancy Counselling

- Multidisciplinary team involvement (obstetrician and hematologist)

- Partner screening

- Stop iron-chelating agents before pregnancy

- Folic acid supplementation (5mg/day) and penicillin prophylaxis for hyposplenism

- Monitoring of Hb and HbS percentage, with transfusion if necessary

Clinical Features

- Hemolytic anemia

- Painful crises

- Hyposplenism

- Increased risk of infections (UTI, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, puerperal sepsis)

- Avascular necrosis of bone

- Increased risk of thromboembolic disease (pulmonary embolism, stroke)

- ACUTE CHEST SYNDROME (FEVER, CHEST PAIN, TACHYPNEA, INCREASE)

- WCC, pulmonary infiltrates

- iron overload leads to cardiomyopathy

Antenatal Care

- Screening for urine infection at each visit

- Treatment of crisis (analgesia, oxygen, rehydration, antibiotics if infection suspected)

- Regular assessment of fetal growth (ultrasound, Doppler)

- Aim for vaginal delivery with adequate hydration, avoiding hypoxia, and continuous fetal monitoringZ - UNLESS CS is indicated

- Consider antenatal and postnatal thromboprophylaxis

- the use of prophylactic antibiotics

Fetal Complications

- Miscarriage

- IUGR

- Prematurity

- Stillbirth

Thyroid Disease and Pregnancy

Thyrotoxicosis:

- 95% of women have graves disease.

- For first time in pregnancy occur in the late first or early second trimester.Z

Clinical features:

- Palpitation.

- Vomiting.

- Goitre.

- Palmer erythema.

- Emotional liabilities.

- Tremors.

- Lid lag.

- Lid retraction.

Diagnosis:

- TFT

Complications

- Maternal complications: hypertension, preeclampsia, heart failure

- Fetal risks:

- Miscarriage.

- IUGR.

- Preterm birth.

- Fetal hypothyroidism(drug induced).Z

- Thyrotoxicosis (in autoimmune cases due to transplacental TSI)

- IUFD.

Management

- Propylthiouracil is better than carbimazole (less teratogenisity).

- Do serial US to monitor the baby.

- Do TFT in each semester.

- Close monitoring during labour”+ continuous CTG”.

- Do cord blood sampling for TFT.

- Delivery is by VD unless CS is indicated

Asthma in Pregnancy

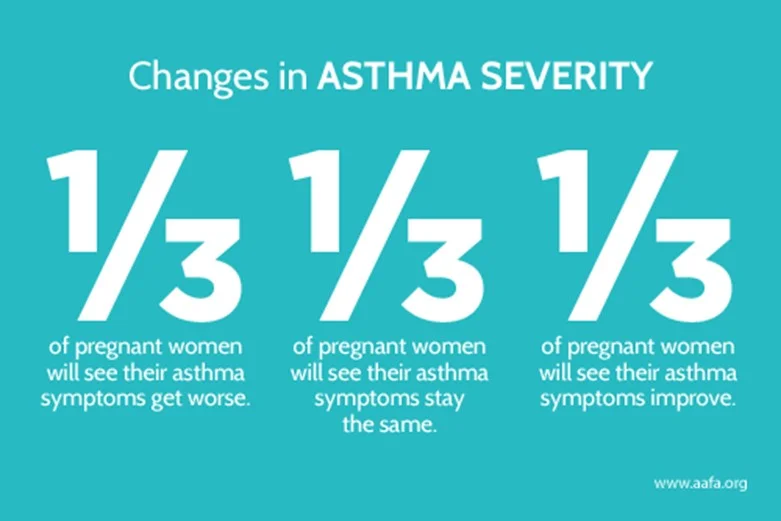

Course of disease

- Approximately one-third of patients worsen during pregnancy, one-third improve, and one-third remain unchanged (pregnancy has no effect).Z

- Most exacerbations occur in the third trimester, but most pregnancies pass uneventfully.

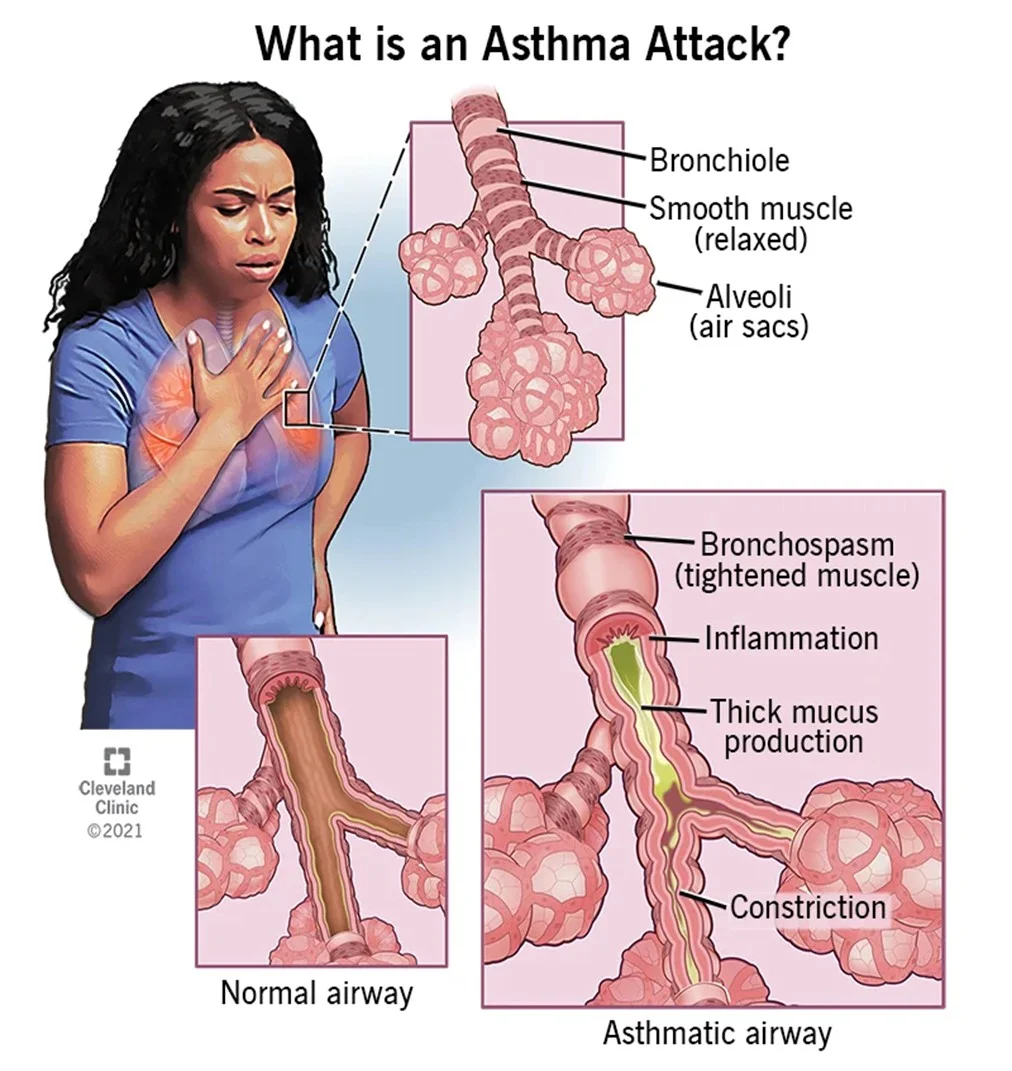

Symptoms

- Cough, wheeze, dyspnoea, chest tightness.

- Avoid known trigger factors.

Common trigger factors

- Pollen, animal dander, dust

- Chest infection, cold weather, emotional stress

Signs of exacerbation

- Tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, audible wheeze, use of accessory respiratory muscles.

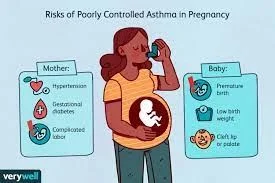

Maternal risks

- Increased risk of preeclampsia, higher maternal mortality, and greater need for hospitalization.

Fetal/neonatal risks

- Low birth weight, preterm delivery, and risk of neonatal asphyxia.

#Z

#Z

Management

- O2.

- Bronchodilator(Salbutamol).(inhaler or oral ).

- Steroids.(oral , inhaler).

- Antibiotics if there is infection.

- Avoid PGs in induction(exacerbate asthma).

- Delivery

VD Unless C/S is indicated.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Definition

- Anaemia in pregnancy: haemoglobin or haematocrit below trimester-specific cut-offs

- 1st trimester: Hb < 11 g/dL, Hct < 33%

- 2nd trimester: Hb < 10.5 g/dL, Hct < 32%

- 3rd trimester: Hb < 11 g/dL, Hct < 33%

Classification (by MCV / mechanism)

- By size (MCV):

- Microcytic (< 80 fL): iron deficiency, thalassaemia (commonly)

- Normocytic (80–100 fL): anaemia of chronic disease, acute blood loss

- Macrocytic (> 100 fL): folate or vitamin B12 deficiency

- By mechanism (often overlapping):

- ↓ Production: iron, folate, B12 deficiency, bone marrow disease

- ↑ Destruction: haemolysis (sickle cell, thalassaemia)

- Blood loss: acute or chronic (menstrual, obstetric, GI)

Risk factors

- Poor dietary intake (low iron/protein/folate)

- Short interpregnancy interval, teenage pregnancy, multiparity

- Heavy menses or prior delivery blood loss

- GI malabsorption, chronic illness

- Hemoglobinopathies (suspect with relevant family history or ethnicity)

Diagnosis

- CBC with indices: Hb, Hct, MCV

- Ferritin: < 30 µg/L confirms iron deficiency

- Peripheral blood smear

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis if hemoglobinopathy suspected

Management

- Lifestyle / nutrition:

- Eat iron-rich foods (red meat, poultry, legumes, leafy greens)

- Vitamin C enhances iron absorption; avoid tea/coffee with meals

- Pharmacological:

- Routine supplementation in pregnancy: ~27 mg/day elemental iron (prenatal vitamins)

- Treatment (oral): ferrous sulfate / ferrous fumarate / ferrous gluconate (dosing depends on elemental iron goal)

- Parenteral iron: for severe anaemia, oral intolerance, or poor response

- Transfusion: reserved for severe cases (e.g., Hb < 6 g/dL with maternal or fetal compromise)

- Practical choices and considerations:

- Ferrous sulfate — first-line: effective, widely available, affordable

- Ferrous gluconate — lower elemental iron, better tolerated (less GI upset) but requires more tablets

- Ferrous fumarate — highest elemental iron per tablet → fewer tablets needed, but may cause more GI side effects

Elemental iron content (approximate per tablet)

- Ferrous fumarate (325 mg): ~106 mg elemental iron

- Ferrous sulfate (325 mg): ~65 mg elemental iron

- Ferrous gluconate (300 mg): ~34 mg elemental iron

Treatment approach (summary)

- Start with ferrous sulfate unless not tolerated.

- If intolerance → switch to ferrous gluconate (gentler).

- If higher elemental dose with fewer pills needed and tolerated → consider ferrous fumarate.

- Use parenteral iron or transfusion for severe / refractory cases or urgent maternal/fetal compromise.

Prevention & screening

- Universal low‑dose iron supplementation from 1st trimester (prenatal vitamins with folate)

- Early screening: CBC at booking and again at 24–28 weeks

Maternal and fetal complications (with emphasis on severe anaemia)

- Maternal: fatigue, reduced work capacity, increased infection risk, higher likelihood of transfusion in obstetric haemorrhage

- Severe anaemia (Hb < 6 g/dL) associated with: abnormal fetal oxygenation, non‑reassuring fetal heart patterns, fetal cerebral vasodilatation, fetal death — may prompt maternal transfusion for fetal indications

- Postpartum: increased risk of postpartum depression, poorer maternal–infant interaction and potential negative effects on infant development

Urinary Tract Infections (UTI)Z

-

Asymptomatic bacteriuria: ~4–8% prevalence; if untreated, ~40% may progress to symptomatic infection.

-

Acute cystitis: ~1% (incidence).

-

Acute pyelonephritis: ~1–2% (incidence).

-

Risk factors

- Female sex, especially with diabetes mellitus

- Sickle cell trait or disease

- Immunosuppression

- Urinary tract stones

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Congenital renal anomalies

-

Typical symptoms

- Pyelonephritis: nausea, vomiting, loin (flank) pain, fever

- Cystitis: suprapubic pain, dysuria

-

Investigations

- Positive urine dipstick should always be followed by a midstream urine (MSU) culture.

-

Management

- All bacteriuria should be treated to prevent pyelonephritis and reduce risk of preterm labor — typically with 3–7 days of a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

- Acute cystitis: treat for 7 days with an appropriate antibiotic.

- Pyelonephritis: treat for 10–14 days with an appropriate antibiotic.

Epilepsy in pregnancy — key points

- Common causes of seizures in pregnancy: epilepsy, eclampsia, encephalitis/meningitis, space‑occupying lesions (tumour, tuberculoma), cerebrovascular accident, cerebral malaria or toxoplasmosis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, drug/alcohol withdrawal, toxic overdose, metabolic abnormalities (e.g. hypoglycaemia).

- Most mothers have healthy babies. Risk of congenital abnormalities depends on the type, number and dose of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Sodium valproate should be avoided in pregnancy because it has a high risk of congenital malformations and adverse neurodevelopmental effects in the child.

Definition, diagnosis and seizure types

- Definition: Epilepsy = recurrent unprovoked seizures, normally diagnosed by a neurologist.

- Common seizure types: tonic–clonic, absence, focal.

- Pregnancy differential diagnosis: eclampsia, metabolic causes, cardiac syncope, psychogenic non‑epileptic seizures, and epilepsy.

Cardiovascular diseases pre-pregnancy counselling

- Lifestyle

- Multidisciplinary with cardiologist 5 mg

- IUGR

- Small for gestational age

- Preterm

Labor

- 1 stage (Cervical diltation + pain) - we give pain killer

- 2 stage (Delivery of baby) - Prophylactic Forceps

- 3 stage (Placental delivery) - Avoid angometr…?

Pre‑pregnancy counselling

- Folic acid: 5 mg/day before conception to reduce neural tube defects.

- AED choice: use the lowest effective dose and avoid valproate and polytherapy where possible.

- Counselling topics: risks of congenital malformations and long‑term neurodevelopmental effects (particularly with valproate). Women who have been seizure‑free for ≥1 year have the best prognosis in pregnancy.

Antenatal management

- Joint obstetrics–neurology care is recommended.

- Screening: detailed anomaly scan at 18–20 weeks; consider serial growth scans if on AEDs.

- AED monitoring: routine serum levels usually not required (exceptions such as lamotrigine in selected cases).

- Obstetric risks: increased risk of miscarriage, hypertensive disorders, haemorrhage and preterm birth.

- Maternal mental health: screen for depression, anxiety and cognitive effects.

- Manage pregnant women with significant heart disease in a joint obstetric/cardiac clinic.

- Continuity of care makes the detection of subtle changes in maternal wellbeing more likely.

- Routine physical examination should include:

- pulse rate.

- blood pressure.

- jugular venous pressure.

- heart sounds.

- ankle and sacral oedema

- and presence of basal crepitations.

- Most women will remain well during the antenatal period.

- Echocardiography is useful in assess function and valves,

- and an echocardiogram at the booking visit and at around 28

- weeks’ gestation is usual.

- Any signs of deteriorating cardiac status should be carefully investigated and treated.

- Anticoagulation is essential in patients with:

- congenital heart disease with pulmonary hypertension (PH).

- or artificial valve replacements.

- and in those at risk of atrial fibrillation.

- Low molecular-weight heparin is often used as an alternative to

- warfarin, especially in the first and third trimester.

Intrapartum care

- Seizure risk in labour is low (~1–2%). Continue AEDs (oral or parenteral as needed).

- Seizure treatment: benzodiazepines are first‑line — treat promptly.

- Analgesia: epidural, Entonox and TENS are safe. Avoid pethidine (can be epileptogenic).

- Delivery: epilepsy alone is not an indication for caesarean section unless there is poor seizure control. Continuous fetal monitoring if seizures occur.

Postpartum management

- Seizure risk ↑ in the first 72 hours postpartum (stress, sleep deprivation, missed doses).

- Review AED dose within ~10 days postpartum to avoid toxicity (physiological changes can alter levels).

- Breastfeeding: encouraged — most AED exposure via milk is compatible with breastfeeding. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam transfer more into milk, but definitive adverse outcomes have not been proven.

- Safety advice: take practical precautions (e.g. baby baths on the floor, don’t bathe alone, general seizure‑safety measures).

- Postpartum depression: more common in women with epilepsy (≈29% vs 11%) — screen all.

Contraception & future pregnancy

-

With enzyme‑inducing AEDs, effective options include copper IUD, levonorgestrel IUS and depot injection; enzyme inducers reduce the efficacy of combined pills, patches, rings and implants.

-

Note: lamotrigine levels can be affected by estrogen contraceptives (dose interactions may increase seizure risk).

-

Emergency contraception: copper IUD preferred when on enzyme‑inducing AEDs.

Management of labour and delivery

- In most cases the aim of management is to await the onset of spontaneous labour.

- Anaesthesia is often recommended to reduces the pain related stress.

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be given to any woman with a structural

- heart defect to reduce the risk of bacterial endocarditis.

- VD is the mode of delivery unless C-section is indicated.

- Caesarean delivery is associated with:

- Risk of haemorrhage, thrombosis and infection, conditions that are likely to be much less

- well tolerated in women with cardiac disease

- the maternal condition is considered too unstable to tolerate the physiological

- demands of labour.. Postpartum haemorrhage in

- particular can lead to major cardiovascular instability. Ergometrine may be

- associated with intense vasoconstriction, hypertension and heart failure, and

- therefore active management of the third stage is usually with Syntocinon™

- (synthetic oxytocin) alone. Syntocinon is a vasodilator and therefore should be

- given slowly to patients with significant heart disease, with low-dose infusions

- preferable. High-level maternal surveillance is required until the main

- haemodynamic changes following delivery have passed

Prepregnancy counselling

- Women with heart disease: will be aware of their condition prior pregnancy

- They should be fully assessed by an obstetrician and cardiologist.

- fetal risks carefully explained.

- A plan to optimize medication & health state.

Issues in pre-pregnancy counselling of women with heart disease

- Risk of maternal death.

- Possible reduction of maternal life expectancy.

- Effects of pregnancy on cardiac disease.

- Mortality associated with high-risk conditions.

- Risk of fetus developing congenital heart disease.

- Risk of preterm labour and FGR.

- Need for frequent hospital attendance and possible admission.

- Intensive maternal and fetal monitoring during labour.

- Other options – contraception, adoption, surrogacy.

- Timing of pregnancy

Fetal risk of maternal cardiac disease

- Recurrence (congenital heart disease).

- Maternal cyanosis (fetal hypoxia).

- Iatrogenic prematurity.

- FGR.

- Effects of maternal drugs (teratogenesis, growth restriction, fetal loss).

Risk factors for development of heart failure in pregnancy

- Respiratory or urinary infections.

- Anaemia.

- Obesity.

- Corticosteroids.

- Tocolytics.

- Multiple gestation.

- Hypertension.

- Arrhythmias.

- Pain-related stress.

- Fluid overload

- Management of labour in women with heart disease

- Avoid induction of labour if possible.

- Use prophylactic antibiotics.

- Ensure fluid balance.

- Avoid the supine position.

- Discuss regional/epidural anaesthesia/analgesia with senior anaesthetist.

- Keep the second stage short.

- Use Syntocinon judiciously.