Neuroplasticity

- The brain’s natural ability to form new connections in order to compensate for injury or changes in one’s environment.

Evidence of Hippocampal Atrophy and Loss in Patients With MDD

- **Compared to controls, patients with depression had smaller hippocampal volumes (n=16)**1

- Decreased hippocampal volume may be related to the duration of depression2−4

- Bremner JD, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115-118.

- Sheline YI, et al. J Neurosci. 1999;19(12):5034-5043.

- Sheline YI, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(9):3908-3913.

- Sheline YI, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516-1518.

Images courtesy of JD Bremner.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Atrophy of the hippocampus, a region of the brain involved in conscious memory, may be associated with depression.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Atrophy of the hippocampus, a region of the brain involved in conscious memory, may be associated with depression.

SPEAKER DIRECTION Molecular and cellular studies of stress, depression, and antidepressants have moved the field of mood disorder research beyond the monoamine hypothesis of depression. These studies demonstrated that stress and antidepressant treatment may exert opposing actions on the expression of specific neurotrophic factors in limbic brain regions involved in the regulation of mood and cognition.1 Most notable are studies of BDNF. The functional significance of altered neurotrophic factor expression was highlighted by studies demonstrating that stress and depression can lead to neuronal atrophy and cell loss in key limbic brain regions implicated in depression, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (which expresses high levels of receptors for glucocorticoids, the major stress reactive adrenal steroid).1 Several studies have associated depression with decreased hippocampal volume.2,3 Furthermore, this reduction in volume has been related to the duration of depression.3-5

BACKGROUND The hippocampus is one of several limbic structures that have been implicated in mood disorders. Included in the functions of hippocampal circuitry are control of learning and memory and regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, both of which are altered in depression. The hippocampus has connections with the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, regions that are more directly involved in emotion and cognition and thereby contribute to other major symptoms of depression.1 Bremner et al studied 16 patients with a history of depression based on the Structured Interview for DSM-IV, finding hippocampal volume loss and memory deficits.2 In a sample of 24 women age 23 to 86 years with histories of recurrent major depression, Sheline et al found that post-depressives scored lower in verbal memory, suggesting that the hippocampal volume loss was related to an aspect of cognitive functioning. The study also found duration of depressive episode to be a predictor of hippocampal volume loss.3

REFERENCES Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116-1127. Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):115-118. Sheline YI, Sanghavi M, Mintun MA, et al. Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. Neurosci. 1999;19:5034-5043. Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, et al. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3908-3913. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC, et al. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160: 1516-1518.

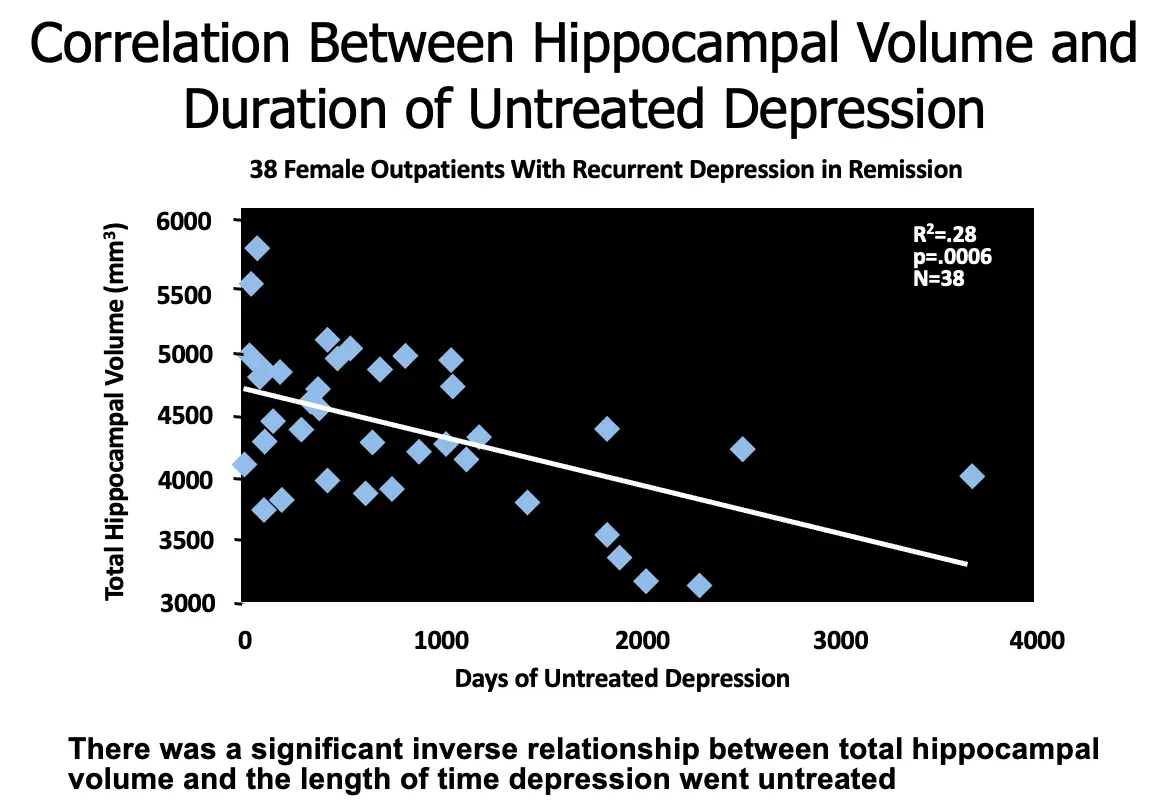

Correlation Between Hippocampal Volume and Duration of Untreated Depression

- 38 Female Outpatients With Recurrent Depression in Remission

- R2 = .28

- p = .0006

- N = 38

There was a significant inverse relationship between total hippocampal volume and the length of time depression went untreated.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Illustrate the potential correlation between the duration of untreated depression and changes in hippocampal volume.

Emphasize the urgency to treat depression early.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Illustrate the potential correlation between the duration of untreated depression and changes in hippocampal volume.

Emphasize the urgency to treat depression early.

SPEAKER DIRECTION In this study, depression that had gone untreated was found to have deleterious effects on overall neuronal health. The duration of time that depression was untreated was significantly inversely related to hippocampal volume, with longer periods of untreated depression correlated with lower total hippocampal volume.

BACKGROUND 38 outpatient female subjects with recurrent depression in remission were recruited for this study. Subjects were screened for medical problems and were specifically screened for incipient dementia. DSM-IV criteria were used to determine past episodes of major depression as well as for exclusion of other psychiatric diagnoses. Hippocampal volumes were measured using MRI scans. Total time treated was not found to be correlated with hippocampal volume.

REFERENCE Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1516-1518.

Beyond the Synapse: Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Depression, and Antidepressants

- Neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons) continues postnatally and into adulthood

- BDNF is associated with the production of new neurons and their growth and development1

- Data suggest that neurogenesis occurs in the hippocampus2

- The hippocampi appear to have important functions related to both mood and memory

- Data from depressed patients have shown reduced hippocampal volume3

- BDNF may influence regulation of mood4

- BDNF is downregulated in MDD and increased with successful antidepressant treatment4,5

- Both serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) are believed to play roles in the modulation of BDNF1,5

- Duman RS, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(7):597-606.

- Gould E, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(9):715-720.

- Sheline YI, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(9):3908-3913.

- Shimizu E, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(1):70-75.

- Maletic V, et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(12):2030-2040.

Image courtesy of Society for Neuroscience.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Stress the importance of BDNF in depression and connect depression and antidepressants with neuronal health through interaction with BDNF.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Stress the importance of BDNF in depression and connect depression and antidepressants with neuronal health through interaction with BDNF.

SPEAKER DIRECTION Neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons) continues postnatally and into adulthood in the brains of many animal species, including humans. One specific area where neurons continue to be born throughout life is in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.1,2 Neurogenesis is regulated by growth factors, including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), that can lead to the development of new cells and help keep them alive. The hippocampi appear to have important functions related to both mood and memory. Sheline compared hippocampal volumes of subjects with a history of major depressive episodes but currently in remission and with no known medical comorbidity (n=10) to matched normal controls (n=10) by using volumetric magnetic resonance imaging.3 BDNF is expressed throughout the brain in glia, monoamine neurons including monoaminergic, GABA, and glutamate neurons.4 Neurotrophic factors such as BDNF are critical for growth and guidance of the developing nervous system, the survival and function of the adult learning system, learning, and memory.4 Depression, in part, results from a loss of neurotrophic support, which leads to atrophy and loss of neurons in the brain. This suggests a role for structural and neurochemical changes in depression. BDNF has been shown to be associated with regulation of mood,5 and in preclinical studies, to be influenced by stress and perception of pain.6 In one study, patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) had significantly lower levels of BDNF compared to control subjects.5 Antidepressant treatment was shown to raise BDNF levels back to normal levels. Both 5-HT and NE are believed to play roles in the modulation of BDNF.1 Antidepressants act in part by inducing neurotrophic effects that reverse the structural changes that may have occurred.4 Antidepressants increase the synaptic levels of NE and 5-HT over the course of weeks or months, suggesting that adaptation or plasticity is necessary for therapeutic response.

BACKGROUND Most neurons in the mammalian brain and spinal cord are generated during the pre- and perinatal periods of development. Nevertheless, neurons continue to be born throughout life in the olfactory bulb, which processes scents, and in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.1 Most existing neurons in the adult brain cannot divide. Some progenitor cells, however, remain, and they retain the capability for further division into new neurons. Apparently, in most parts of the adult brain, something inhibits progenitor cells from dividing to produce new neurons. No one knows exactly why neurogenesis continues in some areas and not others. In a study of 33 patients with MDD, patients who had not received antidepressant treatment (n=16) had significantly lower BDNF levels than treated patients (n=17) as well as control subjects (n=50).5 In an animal study, both stress as well as acute and chronic pain states significantly lowered levels of BDNF mRNA in the rat hippocampus.5 5-HT and/or NE activate intracellular cascades that can independently lead to activation of transcription factor (CREB) and eventual synthesis of BDNF. BDNF interacts with TrkB receptor to enhance neuroplasticity and neurogenesis. By facilitating synthesis of a neuroprotective factor, Bcl-2, BDNF helps improve cellular resilience.7,8

REFERENCES Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ. A molecular and cellular theory of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(7):597-606. Gould E, Tanapat P, Rydel T, Hastings N. Regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis in adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(8):715-720. Sheline YI, Wang PW, Gado MH, Csernansky JG, Vannier MW. Hippocampal atrophy in recurrent major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(9):3908-3913. Duman RS. Role of neurotrophic factors in the etiology and treatment of mood disorders. Neuromol Med. 2004;5:11-25. Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Okamura N, et al. Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(1):70-75. Duric V, McCarson KE. Hippocampal neurokinin-1 receptor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression is decreased in rat models of pain and stress. Neuroscience. 2005;133(4):999-1006. Maletic V, Robinson M, Oakes T, et al. Neurobiology of depression: an integrated view of key findings. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:2030-2040. Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Sporn J, et al. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:707-742.

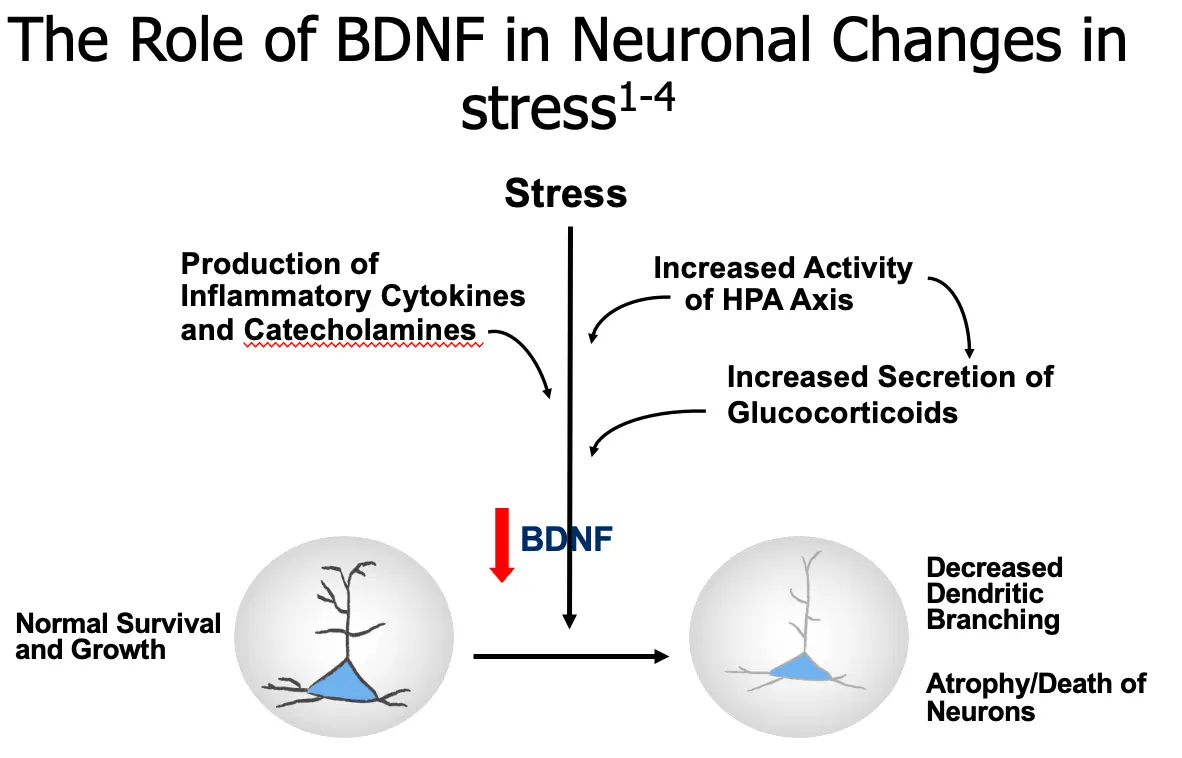

The Role of BDNF in Neuronal Changes in Stress

- Stress

- Production of Inflammatory Cytokines and Catecholamines

- Increased Activity of HPA Axis

- Increased Secretion of Glucocorticoids

BDNF

- Normal Survival and Growth

- Decreased Dendritic Branching

- Atrophy/Death of Neurons

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Show the importance of the HPA axis and BDNF in some of the neuronal changes that may be involved in depression.

PURPOSE OF THE SLIDE

Show the importance of the HPA axis and BDNF in some of the neuronal changes that may be involved in depression.

SPEAKER DIRECTION Molecular and cellular studies of stress, depression, and antidepressants have moved the field of mood disorder research beyond the monoamine hypothesis of depression. Stress has been shown to decrease levels of BDNF in the hippocampus, as well as produce neuronal atrophy and decrease neurogenesis, which may contribute to a depression-like state.1,2 A mechanism by which the brain reacts to stress and depression is activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.3 Sustained elevations of glucocorticoids may be seen under conditions of prolonged, severe stress and possibly in patients with depression, hippocampal neurons may be damaged and reduction of neurogenesis may occur. Patients with major depression who are otherwise medically healthy have also been observed to have activated inflammatory pathways. Activation of macrophages due to inflammatory challenges (infection, tissue damage, or destruction) may cause release of proinflammatory cytokines. These cytokines enter several areas of the afferent sensory systems and can lead to increased activity. Once in the brain, cytokines can cause altered metabolism of serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine (DA), activation of corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) leading to increased serum glucocorticoid levels, and disruption of synaptic plasticity through changes in growth factors such as BDNF.4 Severe stress can cause several changes in these neurons, including a reduction in their dendritic branching, and a reduction in BDNF expression (which could be one of the factors mediating the dendritic effects). The reduction in BDNF is thought to be mediated partly by excessive glucocorticoids, which could interfere with the normal transcriptional mechanisms that control BDNF expression and therefore damage hippocampal pyramidal neurons.2

BACKGROUND The requirement for long-term, chronic antidepressant treatment has led to the hypothesis that alterations in functional and structural plasticity may be necessary for a therapeutic response.1 Antidepressants are thought to produce the opposite effects: they increase dendritic branching and BDNF expression of these hippocampal neurons. By these actions, antidepressants may reverse and prevent the actions of stress on the hippocampus, and therefore may ameliorate certain symptoms of depression.5 Antidepressants have been shown to increase levels of BDNF (as well as other neurotrophic/growth factors). The reversal of neuronal atrophy, increased neurogenesis, and antidepressant response may potentially be regulated by increases in growth factors such as BDNF.

REFERENCES Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116-1127. Sapolsky RM Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57;925-935. Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:580-592. Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends in Immunol. 2006;27:24-31. Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, et al. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34(1):13-25.

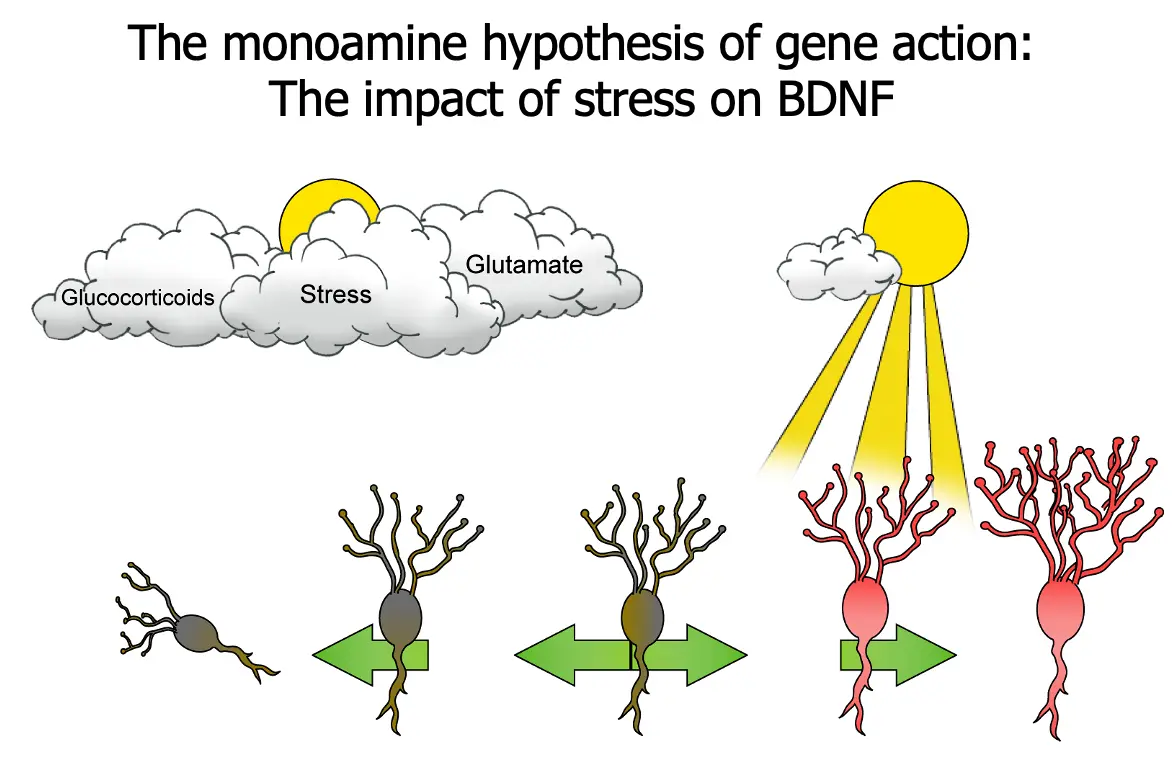

The Monoamine Hypothesis of Gene Action: The Impact of Stress on BDNF

- Glucocorticoids

- Stress

- Glutamate

KEY POINTS

This slide uses the simple idea of a plant that needs sunlight to survive, the absence of which means withering and death.

“One candidate mechanism that has been proposed as the site for a possible flaw in signal transduction from monoamine receptors is the target gene for BDNF.”

“Normally, BDNF sustains the viability of brain neurons. Shown here, however, is the gene for BDNF under situations of stress. In this case, the gene for BDNF is repressed, and BDNF is not being synthesized. If BDNF is no longer made in appropriate amounts, instead of the neuron prospering and developing more and more synapses, stress can cause vulnerable neurons in the hippocampus to atrophy and possibly undergo apoptosis when their neurotrophic factor is cut off.”

“This, in turn, can lead to depression and to the consequences of repeated episodes and less and less responsiveness to treatment. This may explain why hippocampal neurons seem decreased in size and impaired in function during depression, on the basis of recent neuroimaging studies.”

“These findings stress the importance of early detection and diagnosis of depression in order to provide patients the highest chances of optimal outcomes.”

KEY POINTS

This slide uses the simple idea of a plant that needs sunlight to survive, the absence of which means withering and death.

“One candidate mechanism that has been proposed as the site for a possible flaw in signal transduction from monoamine receptors is the target gene for BDNF.”

“Normally, BDNF sustains the viability of brain neurons. Shown here, however, is the gene for BDNF under situations of stress. In this case, the gene for BDNF is repressed, and BDNF is not being synthesized. If BDNF is no longer made in appropriate amounts, instead of the neuron prospering and developing more and more synapses, stress can cause vulnerable neurons in the hippocampus to atrophy and possibly undergo apoptosis when their neurotrophic factor is cut off.”

“This, in turn, can lead to depression and to the consequences of repeated episodes and less and less responsiveness to treatment. This may explain why hippocampal neurons seem decreased in size and impaired in function during depression, on the basis of recent neuroimaging studies.”

“These findings stress the importance of early detection and diagnosis of depression in order to provide patients the highest chances of optimal outcomes.”

REFERENCE Stahl SM. Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000:187.