What is it?

Measles is one of the most contagious communicable diseases. It is caused by the measles virus (paramyxovirus) and is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable deaths in children worldwide.

Signs and Symptoms

- Fever, cough, runny nose, and watery inflamed eyes.

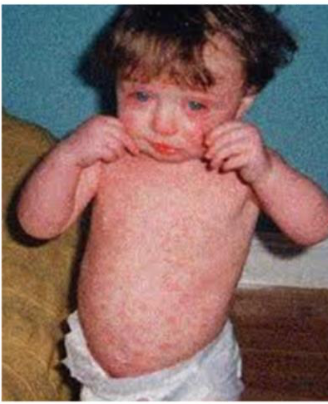

- Rash: The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized, maculopapular, erythematous rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the back of ears and, after a few hours, spreads to the head and neck before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The rash is said to “stain”, changing color from red to dark brown, before disappearing. The measles rash appears two to four days after the initial symptoms and lasts for up to eight days.

- The classical signs and symptoms of measles include four-day fever and the three Cs — cough, coryza (head cold), conjunctivitis (red eyes).

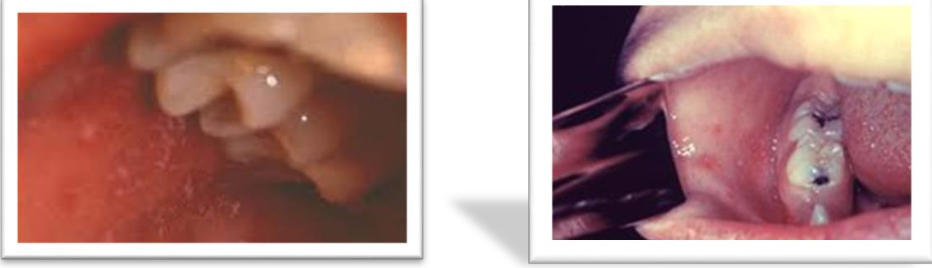

Koplik’s spots seen inside the mouth: small red spots with white or bluish-white centers in the mouth, pathognomonic (diagnostic) for measles, but not often seen because they are transient and may disappear within a day of arising.

How is it spread?

Through the air by droplets that have been coughed, sneezed, or breathed by an infected person. The measles virus can survive in small droplets in the air for several hours.

Incubation Period

Usually about 10 days. Fever usually develops 7 - 18 days after exposure to an infected person. Rash usually develops 14 days after exposure.

When is the person contagious?

From about 5 days before to 4 days after the rash appears.

How to prevent spread of the illness to other children?

- Exclude child from school, child care, and non-family contacts until 4 days after the rash appears.

- It is recommended that all contacts of a measles case who have not had measles disease or 2 doses of measles vaccine receive measles vaccine within 72 hours of last exposure to the infected child.

- All susceptible contacts should stay away from the child care facility or school until they have received one dose of measles vaccine.

- Immunoglobulin is available to prevent measles disease in people who are exposed to a case of measles but who are unable to be immunized for any reason.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) or be excluded from the setting (school, hospital, childcare).

MMR vaccine, if administered within 72 hours of initial measles exposure, or immunoglobulin (IG), if administered within 6 days of exposure, may provide some protection or modify the clinical course of disease.

MMR Vaccine as Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

-

If MMR vaccine is not administered within 72 hours of exposure as PEP, MMR vaccine should still be offered at any interval following exposure to the disease in order to offer protection from future exposures.

-

People who receive MMR vaccine or IG as PEP should be monitored for signs and symptoms consistent with measles for at least one incubation period.

-

If many measles cases are occurring among infants younger than 12 months of age, measles vaccination of infants as young as 6 months of age may be used as an outbreak control measure.

-

Note that children vaccinated before their first birthday should be revaccinated when they are 12 through 15 months old and again when they are 4 through 6 years of age.

-

Except in healthcare settings, unvaccinated people who receive their first dose of MMR vaccine within 72 hours after exposure may return to childcare, school, or work.

Immunoglobulin (IG) as Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

People who are at risk for severe illness and complications from measles, such as infants younger than 12 months of age, pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity, and people with severely compromised immune systems, should receive IG.

- Intramuscular IG (IGIM) should be given to all infants younger than 12 months of age who have been exposed to measles.

Complications

Complications with measles are relatively common, ranging from the relatively mild and less serious ones like diarrhea to more serious ones such as pneumonia, otitis media, acute encephalitis (rarely SSPE — subacute sclerosing panencephalitis), and complications are usually more severe in adults who catch the virus.

- In immunocompromised patients (e.g., people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.

Risk Factors for Severe Measles and Its Complications

- Malnutrition

- Underlying immunodeficiency

- Pregnancy

- Vitamin A deficiency

Diagnosis

- Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days, with at least one of the three C’s (cough, coryza, conjunctivitis). Observation of Koplik’s spots is also diagnostic of measles.

- Alternatively, laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens.

- In patients where phlebotomy is not possible, saliva can be collected for salivary measles-specific IgA testing.

- Positive contact with other patients known to have measles adds strong epidemiological evidence to the diagnosis.

Treatment

- There is no specific treatment for measles. Most patients with uncomplicated measles will recover with rest and supportive Rx.

- Some patients will develop pneumonia as a sequelae to the measles. Other complications include ear infections, bronchitis, and encephalitis. Acute measles encephalitis has a mortality rate of 15%.

- While there is no specific treatment for measles encephalitis, antibiotics are required for bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis that can follow measles.

- All other treatment addresses symptoms, with ibuprofen, or acetaminophen (paracetamol) to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting bronchodilator for cough.

- As for aspirin, some research has suggested a correlation between children who take aspirin and the development of Reye’s syndrome.

- The use of vitamin A in treatment has been investigated. A systematic review of trials into its use found no significant reduction in overall mortality, but it did reduce mortality in children aged under two years.

- Vaccination of measles in Saudi Arabia started at age of 9 months.