IM

By Israa

Introduction

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is an autoimmune inflammatory process that develops as a sequela of streptococcal infection. ARF has extremely variable manifestations and remains a clinical syndrome for which no specific diagnostic test exists. Persons who have experienced an episode of ARF are predisposed to recurrence following subsequent group A streptococcal infections. The most significant complication of ARF is rheumatic heart disease, which usually occurs after repeated bouts of acute illness.

Pathophysiology

ARF is characterized by nonsuppurative inflammatory lesions of the joints, heart, subcutaneous tissue, and central nervous system. An extensive literature search has shown that, at least in developed countries, rheumatic fever follows pharyngeal infection with rheumatogenic group A streptococci.

Molecular mimicry accounts for the tissue injury that occurs in rheumatic fever. Both the humoral and cellular host defenses of a genetically vulnerable host are involved. In this process, the patient’s immune responses (both B- and T-cell mediated) are unable to distinguish between the invading microbe and certain host tissues.

Clinical Manifestation Z

- Subcutaneous nodules, Erythema marginatum (keratin)

- Sydenham’s chorea (Ganglioside protein)

- Pancarditis (laminin, tropomyosin, myosin, actin and troponin)

- Migratory poly Arthritis (vimentin)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of RF is based on JONES criteria. We need two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria in order to diagnose RF.

Jones Criteria, 2015 revision, low-risk populations (United States, Europe, other high-income areas)

Major criteria are as follows: Z

- Carditis (clinical or echocardiographic diagnosis)

- Polyarthritis (not monoarthritis)

- Chorea (rare in adults)

- Erythema marginatum (uncommon; rare in adults)

- Subcutaneous nodules (uncommon; rare in adults)

Minor criteria are as follows: Z

- Polyarthralgia (cannot count arthritis as a major criterion and arthralgia as a minor criterion)

- Fever exceeding 38.5°C

- Elevated ESR (>60 mm/hr) or CRP level (>3 mg/L)

- Prolonged PR interval

Jones criteria, 2015 revision, high-risk populations (Oceania, Africa, South Asia, other lower-income areas)

Major criteria are as follows: Z

- Carditis (clinical or echocardiographic diagnosis)

- Polyarthritis or monoarthritis: Polyarthralgias can also be considered but only after careful consideration of the differential diagnoses.

- Chorea (rare in adults)

- Erythema marginatum (uncommon; rare in adults)

- Subcutaneous nodules (uncommon; rare in adults)

Minor criteria are as follows: Z

- Polyarthralgia (cannot count arthritis as a major criterion and arthralgia as a minor criterion)

- Fever exceeding 38°C (note lower cutoff)

- Elevated ESR (>30 mm/hr; note lower ESR standard) or CRP level (>3 mg/L)

- Prolonged PR interval

Universal criteria

In both higher- and lower-risk settings, evidence of group A streptococcal disease is required for diagnosis, except when rheumatic fever is first discovered after a long latent period (eg, Sydenham chorea, indolent carditis), as follows:

Evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection

- Positive throat culture or rapid antigen test result

- Elevated or rising streptococcal antibody titer

left murmur

Scoring

If supported by evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection, the presence of two major manifestations or one major and two minor manifestations indicates a high probability of ARF. Failure to fulfill the Jones criteria makes the diagnosis unlikely but not impossible. Clinical judgment is required.

Recurrent ARF can be diagnosed based on 2 major, 1 major plus 2 minor, or 3 minor criteria.

Medical Care

Management and prevention of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) can be divided into the following 4 approaches.

1. Treatment of the group A streptococci Treatment of the group A streptococcal infection that led to the disease. Although never proven to improve the one-year outcome, this is a standard practice. It may at least serve to reduce the spread of the causative strain. Z

2. General treatment of the acute episode

-

Anti-inflammatory agents are used to control the arthritis, fever, and other acute symptoms. Salicylates are the preferred agents, although other nonsteroidal agents are probably equally efficacious and maybe preferred in children. Steroids are also effective but should probably be reserved for patients in whom salicylates fail, since there is a risk of rebound when they are withdrawn. None of these anti-inflammatory agents has been shown to reduce the risk of subsequent rheumatic heart disease.

-

Bed rest is a traditional part of ARF therapy and is especially important in those with carditis. Patients are typically advised to rest through the acute illness and to then gradually increase activity; some clinicians monitor the patient’s ESR and restart activity only as it normalizes.

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin has not been shown to reduce the risk of rheumatic heart disease or to substantially improve the clinical course.

-

Chorea is usually managed conservatively in a quiet nonstimulatory environment; valproic acid is the preferred agent if sedation is needed. Intravenous immunoglobulin, steroids, and plasmapheresis have all been used successfully in refractory chorea, although conclusive evidence of their efficacy is limited.

-

Some promising work suggests a possible role for hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of ARF, although no clinical data are yet available to recommend its use.

3. Cardiac management

- Bed rest is essential in patients with cardiac involvement. Carditis resulting in heart failure is treated with conventional measures; some use corticosteroids for severe carditis, although data to support this are scant. Diuretics and vasodilators are the mainstays of therapy.

- Monitor for the development of arrhythmias in patients with active myocarditis. Atrial fibrillation requires aggressive management to reduce the risk of stroke.

4. Prophylaxis

-

Primary prophylaxis (treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis) dramatically reduces the risk of ARF and should be provided whenever a group A streptococcal pharyngitis is confirmed. Treatment of pharyngitis without proof of group A streptococcal etiology may be reasonable in areas of high endemicity.

-

Secondary prevention is recommended to prevent additional streptococcal infections and is believed by most experts to be a critical step in the management of ARF. Patients with a history of rheumatic fever are at a high risk of recurrent ARF, which may further the cardiac damage. The exact duration of chronic antimicrobial prophylaxis remains controversial, but the WHO guidelines are commonly used. There had been concern that sustained benzathine penicillin as secondary prophylaxis would lead to the development of resistant strains of Streptococcus viridans, but a 2008 study found no support for this hypothesis.

- Rheumatic fever with carditis and clinically significant residual heart disease requires antibiotic treatment for a minimum of 10 years after the latest episode; prophylaxis is required until the patient is aged at least 40-45 years and is sometimes continued for life.

- Rheumatic fever with carditis and no residual heart disease aside from mild mitral regurgitation requires antibiotic treatment for 10 years or until age 25 years (whichever is longer).

- Rheumatic fever without carditis requires antibiotic treatment for 5 years or until the patient is aged 18-21 years (whichever is longer).

For secondary prophylaxis penicillin G benzathine at a dose of 1.2 million U IM q4wk is used. Long-term administration of oral penicillin may be used in lieu of the intramuscular route. Erythromycin or sulfadiazine may be used in patients who are allergic to penicillin.

Surgical Care Z

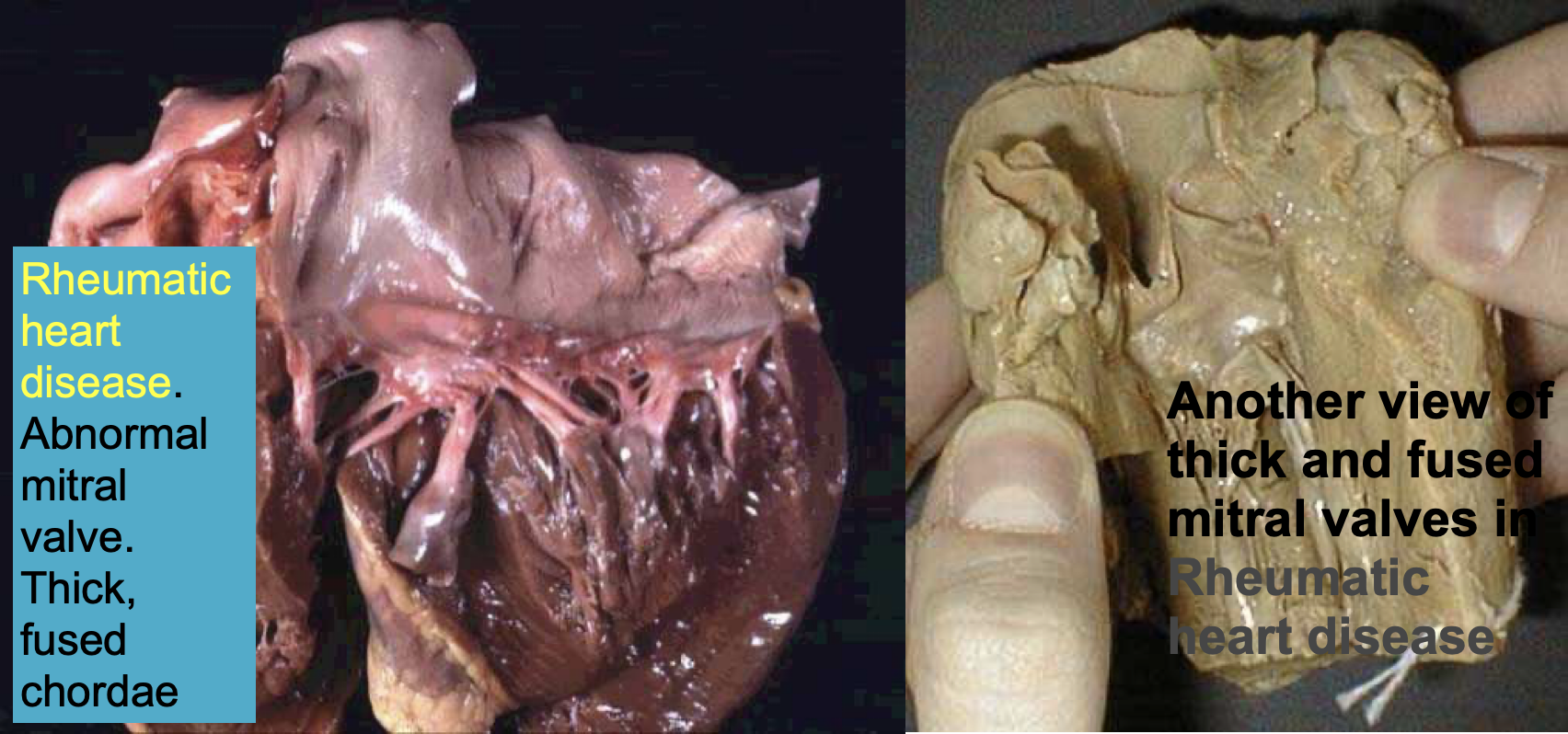

Surgical care is not typically indicated in ARF. Surgical intervention is often required to treat long-term valvular cardiac sequelae of ARF including aortic and mitral regurgitation as well as mitral stenosis.

Pediatrics

ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER

DR MANSOUR M ALQURASHI

Associate professor of Clinical Pediatrics College of Medicine, Imam University, Riyadh

Aetiology

- ARF is an autoimmune disease due to group A streptococcal infection, with a latent period of 2-3 weeks.

- It affects joints, brain, skin, and heart. Molecular mimicry.

- Only the effects on the heart can lead to permanent illness; rheumatic heart disease.

- The risk of ARF after streptococcal pharyngitis is 1-3%. Adequate treatment reduces risk to 70%.

- It may occur after streptococcal pyoderma in tropical regions.

- Primary episodes of ARF occur in children aged 5 to 15 years.

ARF Epidemiology

- Females are more likely to develop Sydenham’s chorea.

- The disease peaks in cooler months of the year.

- Crowding and low socioeconomic status are the main environmental factors favoring the occurrence of ARF.

Jones Criteria (Revised) for Guidance in the Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever*

| Major Manifestation | Minor Manifestations | Supporting Evidence of Streptococcal Infection |

|---|---|---|

| Carditis | Clinical | Increased Titer of Anti-Streptococcal Antibodies ASO (anti-streptolysin O), |

| Polyarthritis | Previous rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease | |

| Chorea | Arthralgia | |

| Erythema Marginatum | Fever | |

| Subcutaneous Nodules | Laboratory | Others |

| Acute phase reactants: | - Positive Throat Culture for Group A Streptococcus | |

| - Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | - Recent Scarlet Fever | |

| - C-reactive protein | ||

| - Leukocytosis | ||

| - Prolonged P-R interval |

*The presence of two major criteria, or of one major and two minor criteria, indicates a high probability of acute rheumatic fever, if supported by evidence of Group A streptococcal infection.

Exceptions of Jones criteria

A presumptive diagnosis of ARF can be made without strict adherence to the revised Jones criteria:

- Chorea as the only manifestation.

- Indolent carditis as the only manifestation in patients who come to medical attention months after acute GAS infection.

- Recurrent rheumatic fever in patients with a history of rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease.

A presumptive diagnosis of recurrent ARF may be made with one major or two minor criteria if there is evidence of a recent GAS infection.

Evidence of Streptococcal Infection

- Positive throat culture for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (25%).

- Positive rapid streptococcal antigen test - specificity of ≥95 percent and a sensitivity 70-90 percent

- Elevated or rising antistreptolysin O antibody titer (80%).

Anti-DNase B, anti-streptococcal-hyaluronidase (ASH), anti-streptokinase antibodies

Minor Manifestations of ARF

- Arthralgia: most common manifestation of ARF; suggest ARF if migratory, asymmetrical, affecting large joints (major in HRP).

- Fever: Temp greater than 38.5°C. (38 high-risk population) Most manifestations of ARF are accompanied by fever

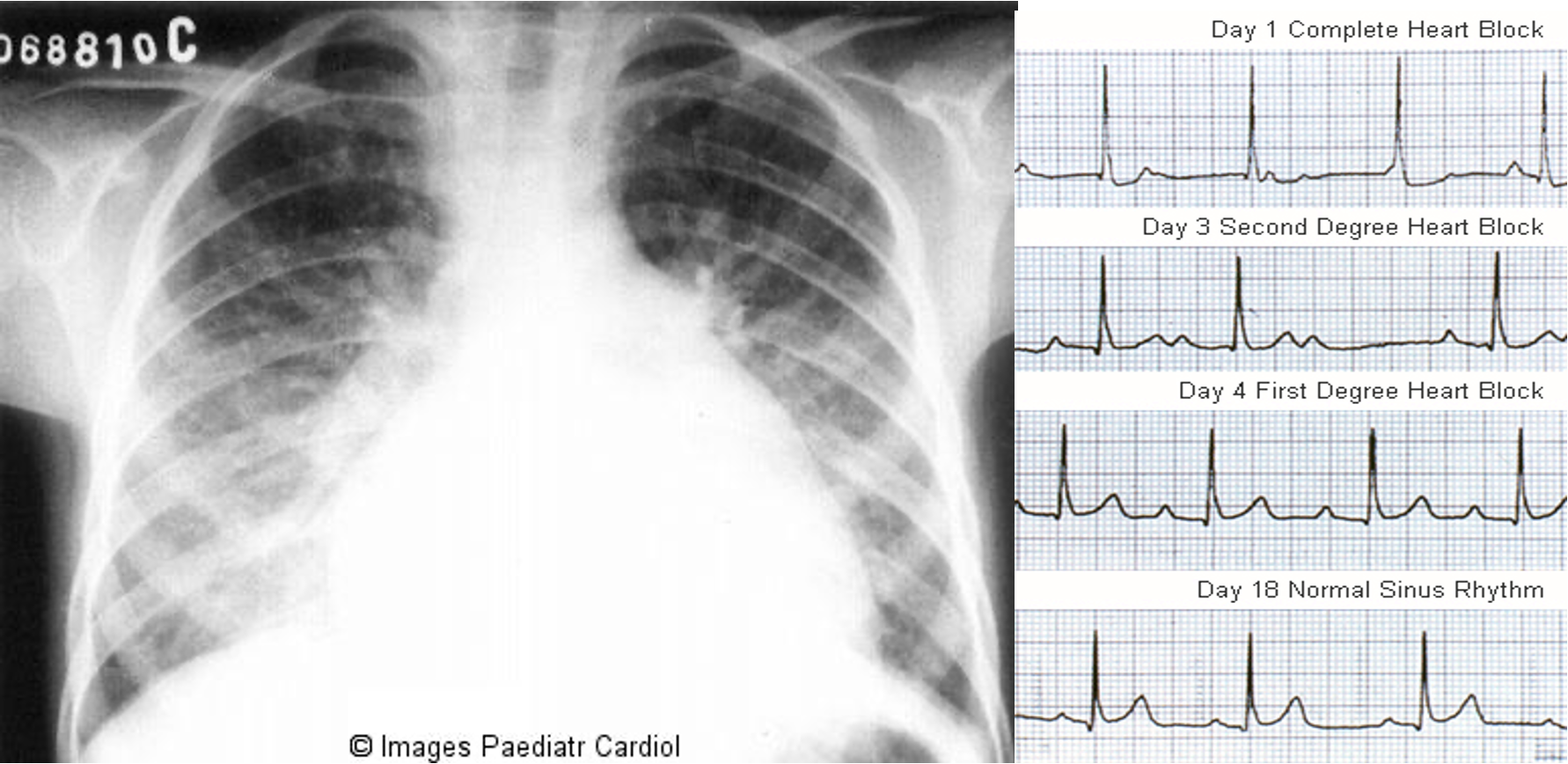

- ECG: If a prolonged P-R interval is detected, the ECG should be repeated after 1-2 months.

- Elevated acute-phase reactants: Serum CRP level of ≥30 mg/L or ESR of ≥60 mm/h (30 in HRP)

- Leukocytosis

High risk: incidence > 2 per 100,000 or prevalence > 1 per 1000

Arthritis

- 60-80%

- Characteristically, migratory polyarthritis pattern is noticed.

- The total duration of polyarthritis is no more than 3 or 4 weeks leaving no residual joint damage.

- Extremely painful, affecting the large joints, especially the ankles and knees, is usually asymmetrical and migratory, but can be additive.

- Joint pain is more prominent than objective signs of inflammation and severely limit movement (swelling, warmth, erythema, limitation of motion, and severe tenderness).

- Responds quickly to salicylates. (Therapeutic test).

- Radiography of an affected joint may show a slight effusion.

- Analysis of the synovial fluid in ARF with arthritis demonstrates sterile inflammatory fluid.

- Monoarthritis may be observed in patients treated with NSAIDs or HRP

Sydenham chorea

- Consists of jerky, uncoordinated movements, especially affecting the hands, feet, tongue, and face; disappears during sleep.

- Other features: Emotional lability, Hypotonia, and Inability to maintain a tetanic muscle contraction.

- Echocardiography is essential for all patients with chorea. (70% carditis and 30% subclinical carditis).

- Chorea usually occurs after a latent period that is longer than that associated with other manifestations of ARF. 10-30%.

Erythema Marginatum

- Pink or faintly red, non-pruritic rash involving the trunk and sometimes the limbs.

- Individual lesions may disappear and reappear in a matter of hours. A hot bath may make them more evident.

- Usually occurs early in the course of ARF in patients with acute carditis. < 6%.

Subcutaneous nodules

- 0.5–2 cm in diameter, round, firm, freely mobile, and painless nodules.

- The overlying skin is not inflamed and can be moved over the nodules

- Occur in crops of up to 12 over the elbows, wrists, knees, ankles, Achilles tendon, occiput, and posterior spinal processes of the vertebrae.

- Appear 1-2 weeks after the onset of other symptoms, last only 1-2 weeks, and are strongly associated with carditis. 0-10%

Carditis

- Incidence of carditis in initial attacks of ARF 50-80%.

- Evidence of carditis can be found at presentation, along with fever and arthritis (commonly).

- Rheumatic fever causes pancarditis.

- Pericarditis: pericardial friction rub and effusion.

- Myocarditis: Cardiomegaly, CHF, Sinus tachycardia, heart block. Rapid sleeping pulse rate.

Endocarditis

- Valvulitis: auscultatory findings and echo evidence of mitral or aortic regurgitation.

- Doppler identification of MR/AR alone is not diagnostic of rheumatic valvulitis.

- Characteristic murmurs of acute carditis include:

- High-pitched, blowing, holosystolic, apical murmur of MR.

- Low-pitched, apical, mid-diastolic, flow murmur (Carey-Coombs murmur).

- High-pitched, diastolic murmur of AR heard at the aortic area.

Additional features

- Family history

- Abdominal pain, precordial pain, malaise.

- Epistaxis.

- Anemia (mild normocytic normochromic).

- Normal complement level.

Investigations

- WBC

- ESR, CRP

- ECG

- Chest X-ray

- Echo.

Throat swab culture for group A streptococcus

ASO and anti-DNase B titres (repeat 10-14 days later if first test not confirmatory)

Chest radiograph of an 8 year old patient with acute carditis before treatment

Chest radiograph of an 8 year old patient with acute carditis before treatment

Treatment

- Bed rest for inflamed joints and/or congestive heart failure (CHF).

- Specific therapy for CHF e.g. diuretics.

- Oral penicillin for 10 days to eradicate throat streptococci.

- Aspirin/Naproxen is effective in decreasing fever and joint inflammation.

Corticosteroids are reserved for:

- Patients with severe carditis manifested by CHF.

- Patients who are unable to tolerate large doses of aspirin.

- Patients whose signs and symptoms are not adequately suppressed by aspirin.

Patients with significant Sydenham’s chorea need specific treatment: Sodium valproate

ARF Prophylaxis

Primary prophylaxis of ARF: Treatment of streptococcal throat infections.

Secondary prophylaxis: To prevent the recurrence of ARF. Benzathine penicillin IM every 3-4 weeks.

It should be maintained indefinitely for those with RHD. Other rheumatic subjects should be protected until they reach age 21 and 5 years have elapsed since the last rheumatic attack, whichever is longer. - Oral penicillin, for patients with RHD at elevated risk (severe valvular heart disease with or without reduced ventricular function).

Bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis for patients with rheumatic heart disease.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Poststreptococcal reactive arthritis:

- Short latent period (1 week).

- Poor response of arthritis to aspirin.

- No carditis but arthritis is marked.

- Tenosynovitis and renal abnormalities are seen.

- ESR, C-reactive protein are lower than ARF.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Brucellosis.

-

Lyme disease

Thera

Incidence

- Age: 5-15 years Rare <3 yrs

- High-risk groups: -poor living conditions, -Overcrowding, -genetic factors.

- No sex difference in the incidence or pathogenesis. But Girls>boys in chorea.

- Common in 3rd world countries

- Environmental factors— over crowding, poor sanitation, poverty,

- Incidence more during fall ,winter & early spring

- Genetic predisposition plays an important role.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Predisposing factors:

- Positive family history.

- More with recurrent streptococcal infection of the throat.

Clinical picture: Rheumatic fever licks the joints but bites the heart.

Pathologic lesions

Fibrinoid degeneration of connective tissue,inflammatory edema, inflammatory cell infiltration & proliferation of specific cells resulting in formation of Ashcoff nodules, resulting in-

- -Pancarditis in the heart

- -Arthritis in the joints

- -Ashcoff nodules in the subcutaneous tissue

- -Basal gangliar lesions resulting in chorea

Clinical Features

1) Arthritis

- *fleeting migratory polyarthritis i.e joint inflammation is followed by joint resolution, then another joint become inflamed followed by resolution and so on., involving major joints which lasts 1-5 weeks and leave joints without sequels and responds to salisylate.

- Commonly involved joints-knee,ankle,elbow & wrist

- Occur in 80%, involved joints is painful, tender, hot & swollen.

- are tender.

- In children below 5 yrs arthritis usually mild but carditis more prominent

- Arthritis do not progress to chronic disease

2) Carditis

Best diagnosis is by echocardiography, must be treated aggressively

- Manifest as pancarditis (endocarditis, myocarditis and pericarditis), occur in 40-50% of cases.

- Carditis is the only manifestation of rheumatic fever that leaves a sequelae & permanent damage to the organ

- Valvulitis occur in acute phase

- Chronic phase- fibrosis, calcification & stenosis of heart valves (fishmouth valves) -

3) Syndenham Chorea

- Occur in 5-10% of cases

- Mainly in girls.

- May appear even 6/12 months after the attack of rheumatic fever.

- Complete resolution of the symptoms typically occurs with improvement in 1-2 weeks and full recovery in 2-3 months.

- Clinically manifest as- deterioration of handwriting, emotional lability or grimacing of face

- Clinical signs- (Emotional liability, school problem, patient is unable to keep his tongue protruded and unsupported by his teeth, grimacing, jerking of the shoulders, and shaking of hands and feets).

- (rapid involuntary purposeless movements);

- it is due to inflammation of the basal ganglia. The condition is reversible

4) Erythema Marginatum

- Occur in <5%.

- Unique,transient,looking lesions of 1-2 inches in size

- Pale center with red irregular margin

- More on trunks & limbs & non-itchy

- Worsens with application of heat

- Often associated with chronic carditis

5) Subcutaneous Nodule

- Occur in 10%, reversible

- Painless,pea-sized,palpable nodules

- Mainly over extensor surfaces of joints,spine,scapulae & scalp

- Associated with strong seropositivity

- Always associated with severe carditis

6) Other Minor Features

-

Fever: above 39°C with no characteristic pattern are initially present in almost every case of acute rheumatic fever.

-

Arthralgia

-

Pallor

-

Anorexia

-

Loss of weight

N.B

- Abdominal pain usually occurs at the onset of acute rheumatic fever.

- Epistaxis may be associated with severe rheumatic carditis.

Clinical Manifestations - “John’s criteria”:

A. Major criteria: 2 major

- Polyrthritis (70%)

- Carditis (50%)

- Rheumatic chorea (10%)

- Subcutaneous nodules (5%).

- Erythema marginatum

B. Minor criteria:

- Arthralgia

- Fever.

- ↑ PR interval in the ECG.

- Lab tests:↑ antistreptolysin O titre (ASO). >200 Todd units.(Peak value attained at 3 weeks,then comes down to normal by 6 weeks)

- ↑ C-reactive protein.

- ↑ ESR.

- Anemia, leucocytosis

- Throat culture-GABHstreptococci

N.B. Exceptiona of John’s Criteria:

-

Chorea alone, if other causes have been excluded

-

Insidious or late-onset carditis with no other explanation

-

Patients with documented RHD or prior rheumatic fever, one major criterion, or of fever, arthralgia or high CRP suggests recurrence

Imaging Study

-

Chest X ray: Cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and other findings consistent with heart failure may be seen on chest radiography.

-

Doppler-echocardiogram: valve edema, mitral regurgitation, LA & LV dilatation, pericardial effusion, decreased contractility

-

Heart catheterization

-

ECG: prolonged PR interval, 2nd or 3rd degree blocks,ST depression, T inversion