IM

Dr. Isra

General Characteristics

This refers to inflammation of the meningeal membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord.

It is usually associated with infectious causes, but noninfectious causes (such as medications (SLE, Sarcoidosis, and carcinomatosis) also exist.

Pathophysiology

Infectious agents frequently colonize the nasopharynx and respiratory tract. These pathogens typically enter the CNS via one of the following:

-

Invasion of the bloodstream, which leads to hematogenous seeding of CNS.

-

Retrograde transport along cranial (e.g., olfactory through cribriform plate).

-

Contiguous spread from sinusitis, otitis media, surgery, or trauma.

*cavernous sinus thrombosis infection*

Classification

Can be classified as acute or chronic, depending on onset of symptoms.

- Acute meningitis—onset within hours to days.

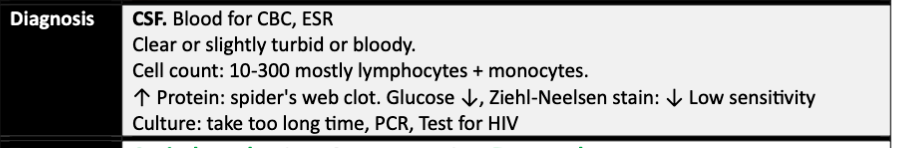

- Chronic meningitis—onset within weeks to months; commonly caused by mycobacteria; TB, fungi (steroid hiv surgery genetic immunodeficiency; sle ibs), Lyme disease, or parasites

Another important distinction is bacterial versus aseptic.

Causes of Acute Bacterial Meningitis

-

Neonates— Group B streptococciZ , <2w E. coli (Vertical), L. monocytogenes (Placenta/milk)

-

Children >3 months— S. pneumoniaeY, Neisseria meningitidisZ, H. influenzae

-

Adults (ages 18 to 50)— S. pneumoniaeZ , N. meningitidisY, H. influenzae

-

Elderly (>50)— S. pneumoniaeZ, N. meningitidisY, L. monocytogenes, gram-negative bacilli.

-

Immunocompromised— S. pneumoniae, L. monocytogenesZ , gram-negative bacilliY, Fungal Meningitis

Acute bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency requiring prompt recognition and antibiotic therapy. It is frequently fatal, even with appropriate treatment.

Complications

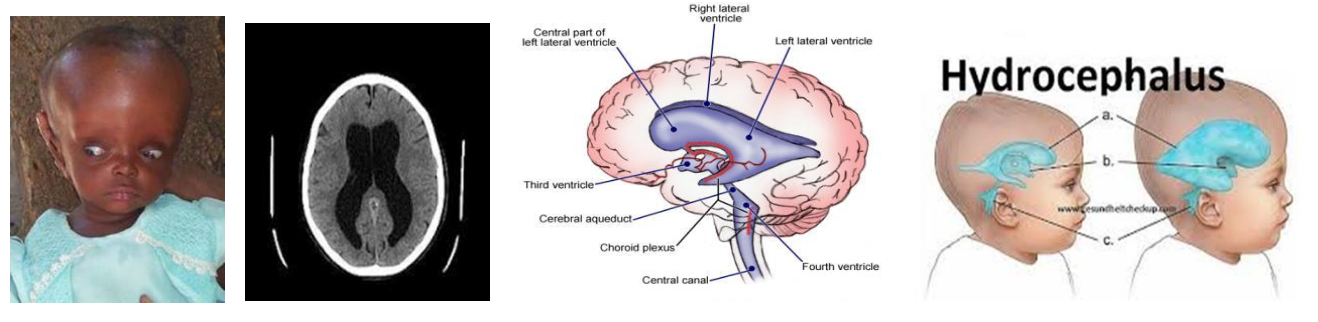

- Acute complications: Seizures, coma, brain abscess, subdural empyema, DIC, respiratory arrest.

- Permanent sequelae: Deafness/Blindness (healing by fibrosis), brain damage, and hydrocephalus in children and increased ICP in adults.

Note: Cushing reflex? (Increase cranial pressure by any reason results increase in BP ⇒ Bradycardia)CCZ SYLVIUS EXPCCZ

Amphroticin; Nephrotoxic; Fungal endocarditis… meningitis Treat

Aseptic Meningitis

Aseptic meningitis is mostly caused by a variety of nonbacterial pathogens, frequently viruses such as enterovirus and herpes simplex virus (HSV).

It can also be caused by certain bacteria, parasites, and fungi.

It may be difficult to distinguish it clinically from acute bacterial meningitis.

If there is uncertainty in diagnosis, treat for acute bacterial meningitis. It is associated with a better prognosis than acute bacterial meningitis

Clinical Features (Symptoms)

(any of the following may be present)

- Headache (may be more severe when lying down)

- Fevers

- Nausea and vomiting

- Stiff, painful neck

- Malaise

- Photophobia

- Alteration in mental status (confusion, lethargy, even coma)

Clinical Features (Signs)

(any of the following may be present)

-

Nuchal rigidity: stiff neck, with resistance to flexion of spine (may be absent)

-

Rashes:

-

Increased ICP and its manifestations—for example, papilledema, seizures

Clinical Features (Meningeal Signs)

-

Kernig sign—inability to fully extend knees when patient is supine with hips flexed (90 degrees) caused by irritation of the meninges. Only present in approximately half of patients with bacterial meningitis

-

Brudzinski sign—flexion of legs and thighs that is brought on by passive flexion of neck for same reason as above; also present in only half of patients with bacterial meningitis

-

Jolt test—worsening headache when patient is asked to turn head back and forth quickly at frequency of at least 3 turns per second. Most sensitive and specific for acute bacterial meningitis.

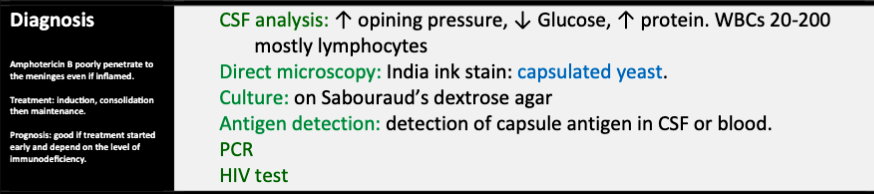

Diagnosis

-

CSF examination (LP)— Perform this if meningitis is a possible diagnosis unless there is evidence of a space-occupying lesion.

-

Examine the CSF color: Cloudy CSF is consistent with a pyogenic leukocytosis. In aseptic meningitis CSF appear normal. -

-

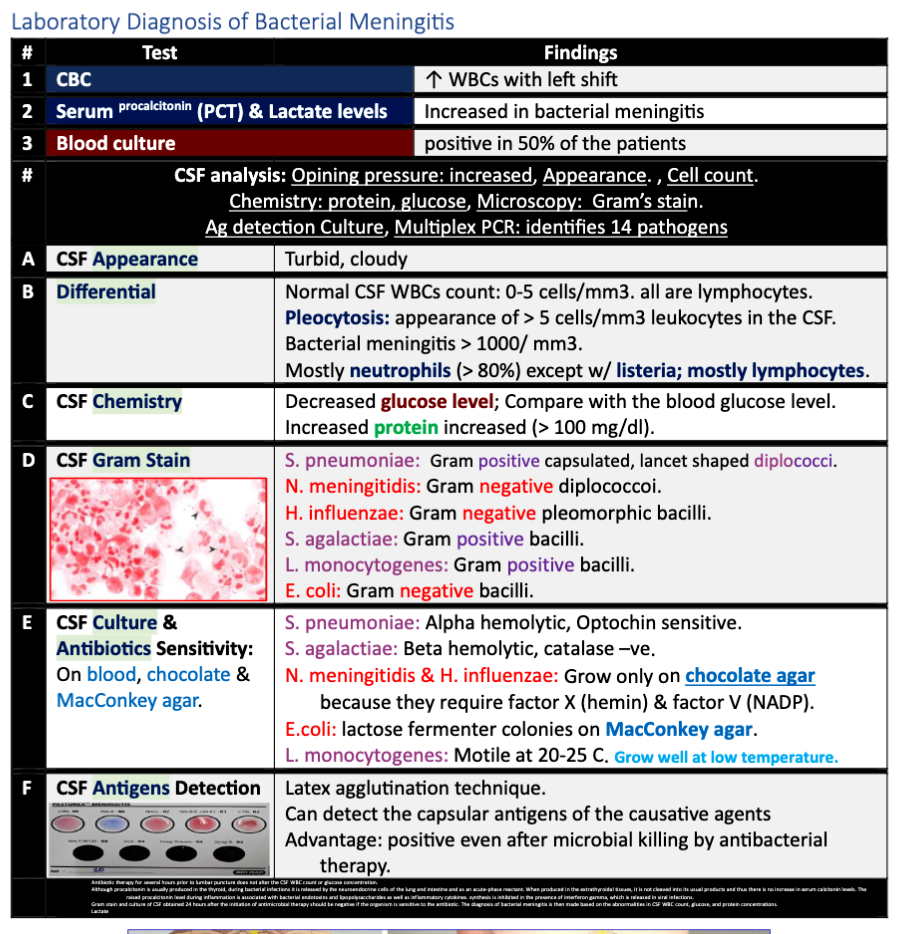

CSF should be sent for the following: cell count, chemistry (e.g., protein, glucose), Gram stain, culture (including AFB), and cryptococcal antigen; Immunocompromised or India ink; Immunocompromised

- Bacterial meningitis—pyogenic inflammatory response in CSF.

-

Elevated WBC count—Neutrophils predominate, Low glucose;(mycobacterium), High protein. ((TB; Lymphocytes-bacterial/Viral))

-

Gram stain—positive in 75% to 80% of patients with bacterial meningitis.

-

+++ Cloudy, Viscous; TB

-

Cloudy; Bacterial or TB

-

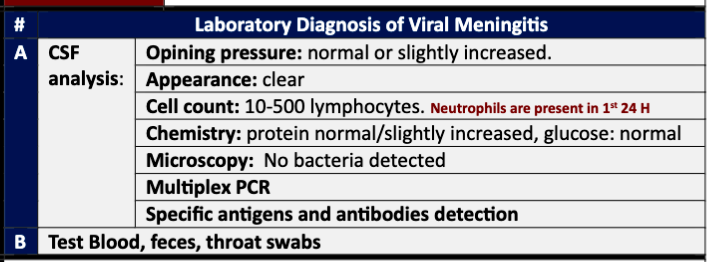

- Aseptic meningitis—nonpyogenic inflammatory response in CSF.

- There is an increase in mononuclear cells. Typically, a lymphocytic pleocytosis is present.

- Protein is normal or slightly elevated. Glucose is usually normal.

Method L3 - L4 - 4 vial Indication:

- Therapeutic; anesthesia, antibiotic, treat idiopathic Intra cranial hypertension; vitamin A, tetracyclines

- Diagnostic; Meningitis, encephalitis

Contraindication of CSF

- No Consent + CT SCAN; SOL + Others; Deformity of site, Bleeding disorders

-

-

CT scan of the head is recommended before performing an LP if there are focal neurologic signs or if there is evidence of a space-occupying lesion with elevations in ICP.

-

Obtain blood cultures before antibiotics are given.

Treatment

Bacterial meningitis:

- Empiric antibiotic therapy—Start immediately after LP is performed. If a CT scan must be performed or if there are anticipated delays in LP, give antibiotics first. Pathogen can often still be identified from CSF several hours after administration of antibiotics.

- Intravenous (IV) antibiotics: Initiate immediately if the CSF is cloudy or if bacterial infection is suspected. Begin empiric therapy according to the patient’s age. Modify treatment as appropriate based on Gram stain, culture, and sensitivity findings.

- Steroids—if suspect S. pneumoniae as causative organism to prevent cerebral edema.

- Analgesics and fever reduction may be appropriate.

Aseptic meningitis: No specific therapy other than supportive care is required. The disease is self-limited.

| Age or Risk Factor | Likely Etiology | Empiric Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 1- Infants (<3 months) | Group B streptococci, E. coli, Klebsiella spp., L. monocytogenes | Cefotaxime + ampicillin + vancomycin (aminoglycoside if <4 weeks) |

| 2- 3 months–50 yrs | N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime + vancomycin //////// |

| 3- >50 yrs | S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, L. monocytogenes, and Gram-negative bacilli | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime + vancomycin + ampicillin |

| 4- Impaired cellular immunity (e.g., HIV) | S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, L. monocytogenes, and aerobic gram-negative bacilli (including P. aeruginosa) | Ceftazidime + ampicillin + vancomycin |

CC S= Vancomycin? N= Cephalosporins; ximexone L=Ampicillin

Vaccination and Prophylaxis

- Vaccinate all adults >65 years for S. pneumoniae; COPD - every 5yrs

- Vaccinate asplenic patients for S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, and H. influenzae (encapsulated organisms).

- Vaccinate immunocompromised patients for N. meningitidis.

- Prophylaxis (e.g., Rifampin; TB or ceftriaxone: N.M)—for all close contacts of patients with meningococcus.

Bacterial

TBM

Viral

Fungal

Pediatrics

What is Meningitis?

Meningitis is an inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, known collectively as the meninges. It can be caused by bacteria, viruses, other microorganisms, and less commonly by certain drugs. Bacterial meningitis is considered a medical emergency as it can progress rapidly due to its proximity to the brain and spinal cord. It can lead to brain damage or even be fatal despite the availability of the most advanced medical care. Timely treatment with appropriate antimicrobial and supportive therapy in acute bacterial meningitis can improve prognosis.

Causes

Bacterial Causes

-

Neonatal Meningitis:

- Group B beta-hemolytic streptococcus (Group B strep)

- Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- Rare cases: Listeria monocytogenes (Listeria)

-

In Children:

- Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib)

- Neisseria meningitides

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Group B Streptococcus

- Staphylococci, Pseudomonas & other gram-negative bacteria (skull trauma, shunt, immunodeficiency)

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis (endemic, persons with immune problems, such as AIDS)

Viral Causes

About 90% of cases of viral meningitis are caused by enteroviruses, such as coxsackieviruses and echoviruses.

Polioviruses, mumps virus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus can also cause viral meningitis.

Fungal Causes

- Cryptococcal meningitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans (common in immunosuppressants Rx, organ transplantation, HIV/AIDS).

Parasitic Causes

- Angiostrongylus cantonensis - most common

- Gnathostoma spinigerum

- Schistosoma

Non-Infectious Causes

- Malignant or neoplastic meningitis

- Drugs: Mainly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, cephalexin, metronidazole, amoxicillin, penicillin, isoniazid), ranitidine, carbamazepine & IV immunoglobulins (cerebral vasospasm or ischemic encephalopathy - reported with IVIG)

- Vaccines against hepatitis B and mumps

- Several inflammatory conditions, such as sarcoidosis (neurosarcoidosis)

- Connective tissue disorders (SLE)

Signs and Symptoms

High fever, headache

-

Infants < 2 years may appear slow or inactive, vomit, or feed poorly

-

Other symptoms: nausea, vomiting, photophobia (discomfort looking into bright lights), phonophobia (discomfort with loud noises), confusion, and sleepiness

-

Seizures may occur as illness progresses

-

Small children may only be irritable and look unwell

-

Rash may indicate a particular cause of meningitis (e.g., meningococcal bacteria may be accompanied by a characteristic rash)

-

Stiff neck common in anyone over the age of 2 years

Other signs of meningism include the presence of

- Positive Kernig’s sign: pain limits passive extension of the knee. A positive.

- Brudzinski sign: occurs when flexion of the neck causes involuntary flexion of the knee and hip

Incubation Period

- Enteroviruses: About 3–7 days

- Bacteria (e.g., meningococcal meningitis): Specific incubation periods vary

Contagious Period

- Enteroviruses: From about 3 days after infection to 10 days after developing symptoms

Diagnosis

-

Complete blood count

-

C-reactive protein

-

Blood cultures

-

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid through lumbar puncture (LP, spinal tap) showing high WBC, low glucose in bacterial meningitis

-

Lumbar puncture contraindicated if there is a mass in the brain or elevated intracranial pressure (ICP)

-

CT or MRI scan recommended if raised ICP is suspected before LP

-

Antibiotics should be administered first if CT or MRI is required before LP

-

Monitoring of blood electrolytes is important (e.g., hyponatremia common in bacterial meningitis)

csf findings in different forms of meningitisCC

Meningococcal Meningitis

What is Meningococcal Meningitis?

Meningococcal meningitis is an infection of the lining of the brain caused by Neisseria meningitidis. It can cause serious illness and death, with a case fatality rate of 8–15%.

The bacteria can be found in the nose and throat of 5% to 10% of people at any time. Meningococcal bacteria also cause septicemia, pneumonia, and conjunctivitis.

Symptoms

- Fever

- Intense headache

- Nausea and often vomiting

- Bulging fontanelle in infants

- Stiff neck

- Stiff back in older children

- Pinpoint rash

Diagnosis

Confirmed with a test of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Incubation Period

Range is 2–10 days (usually 3–4 days) from contact with an infected person to onset of fever.

Contagious Period

From 7 days prior to the onset of symptoms until 24 hours after antibiotics are started.

Complications

- Brain tissue swelling, increased skull pressure, brain herniation

- Decreasing level of consciousness, loss of pupillary light reflex, abnormal posturing

- Obstruction of normal CSF flow (hydrocephalus)

- Seizures, especially in children

- In children, seizures are common in the early stages of meningitis (in 30% of cases) and do not necessarily indicate an underlying cause.

- Seizures may result from increased pressure and from areas of inflammation in the brain tissue.

- Focal seizures (seizures that involve one limb or part of the body), persistent

- seizures, late-onset seizures and those that are difficult to control with medication indicate a poorer long-term outcome.

- Cranial nerve abnormalities

- Visual symptoms and hearing loss

- Inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or its blood vessels (cerebral vasculitis) - as well as formation of Blood clots in veins (cerebral venous thrombosis)

Treatment

-

Meningitis is potentially life-threatening and has a high mortality rate if untreated; delay in treatment has been associated with a poorer outcome. Thus, treatment with wide-spectrum antibiotics should not be delayed while confirmatory tests are being conducted even before the results of the lumbar puncture and CSF analysis are known.

-

The choice of initial treatment depends largely on the kind of bacteria that cause meningitis in a particular place and population. Third generation cephalosporins such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone.

-

If resistance to cephalosporins (found in streptococci), addition of vancomycin to the initial treatment is recommended.

-

In young children, as well as those who are immunocompromised, the addition of ampicillin is recommended to cover Listeria monocytogenes.

-

Once the Gram stain results become available, and the broad type of bacterial cause is known, it may be possible to change the antibiotics to those likely to deal with the presumed group of pathogens.

-

For an antibiotic to be effective in meningitis it must not only be active against the pathogenic bacterium but also reach the meninges in adequate quantities; some antibiotics have inadequate penetrance and therefore have little use in meningitis.

Steroids treatment

-

Adjuvant treatment with corticosteroids (usually dexamethasone) has shown some benefits, such as a reduction of hearing loss, and better short term neurological outcomes.

-

Corticosteroid just before the first dose of antibiotics is given, and continued for four days.

-

Corticosteroids are recommended in the treatment of pediatric meningitis if the cause is H. influenzae, and only if given prior to the first dose of antibiotics; other uses are controversial, like pneumococcal meningitis.

-

They also appear to be beneficial in those with tuberculosis meningitis.

-

Viral meningitis typically only requires supportive therapy; most viruses responsible for causing meningitis are not amenable to specific treatment.

-

Herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus may respond to treatment with antiviral drugs such as acyclovir, but there are no clinical trials that have specifically addressed whether this treatment is effective.

Prognosis

- The prognosis depends on several other factors such as age, presence of comorbidity, causative pathogen, and severity at presentation.

- Neurologic problems such as permanent mental impairment, paralysis, seizures, and hearing loss occur in about 15% of children who survive bacterial meningitis. About 20% of children may experience more subtle adverse outcomes such as cognitive, academic, and behavioral problems.

- Decreased level of consciousness or an abnormally low count of white blood cells in the CSF has poorer prognosis.

- Meningitis caused by H. influenzae and meningococci has a better prognosis than cases caused by group B streptococci, coliforms, and S. pneumonia.

- If the patient develops encephalitis (brain gets infected with the virus) or other complications such as pericarditis and hepatitis, prognosis becomes poor.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Following an Exposure to Meningitis for Healthcare Workers

- Preventative antibiotics are of no use following exposure to meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, Cryptococcal meningitis, viral (aseptic) meningitis.

- Antibiotics are occasionally useful following exposure to patients with Haemophilus influenzae & Neisseria meningitidis meningitis.

- Indications for antibiotics following exposure to a case of meningococcal meningitis are few, especially for healthcare workers.

- Antibiotics are of benefit to those living in households with cases. These household contacts have prolonged and more extensive contact with the affected patient than healthcare workers.

- Administration of antibiotics is occasionally of benefit to healthcare workers. It is advisable in individuals who have performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation or endotracheal intubation on a known or suspected case of meningococcal disease. Otherwise, healthcare workers are not at increased risk of acquiring disease or of taking it home to family members.

A Few Facts to Support This Reasoning

- Chronic asymptomatic carriage of Neisseria meningitidis in the population is common. 5-10% of people carry the germ in the nasopharynx. As such, a person is probably exposed to it all the time. Few people actually become sick.

- Antibiotics used to prevent meningitis can have serious, even fatal side-effects. Some are contraindicated in pregnancy. Some may lessen the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.

Effective Antibiotics Regimens Include

- Rifampin orally twice daily for two days

- Ciprofloxacin orally as a single dose

- Ceftriaxone 250mg as a single intra-muscular injection

Contact Prophylaxis for Invasive Hib Disease

-

Index case and all household contacts if household includes other children <4 years of age who are not fully immunized.*

-

Index case and all household contacts in households with any infants <12 months of age, regardless of immunization status.

-

Index case and all household contacts in households with a child 1–5 years of age who is inadequately immunized.

-

Index case and all room contacts, including staff, in a childcare group if index case attends >18 hours per week and any contacts <2 years of age who are inadequately immunized.

AND children who are not up to date with Hib should be immunized.

Effective Antibiotics Regimens Include

- Rifampicin 20 mg/kg (max 600 mg) PO daily for 4 days, Infants <1 month: 10 mg/kg

- Pregnancy/contraindication to Rifampicin: Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM daily for 2 days

ENT

Meningitis

- Definition: Inflammation of meninges (pia & arachnoid).

- Pathology: Occurs during acute exacerbation of chronic unsafe middle ear infection.

Clinical Picture

- General symptoms and signs:

- High fever, restlessness, irritability

- Photophobia, and delirium

- Signs of meningeal irritation

Diagnosis

- Lumbar puncture is diagnostic.

Treatment

- Treatment of the complication itself and control of ear infection:

- Systemic antibiotics

- Mastoidectomy to control the ear infection

Therapeutics

- Headache

- Stiff neck

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Photophobia

- Drowsiness

- Confusion