Short Stature in Children

Dr. Mansour Alqurashi

Definition

Short stature is defined as:

- Height below the 3rd percentile for age and sex (-1.88 SD).

- More than 2 standard deviations below the mean height for the population (2.3 percentile).

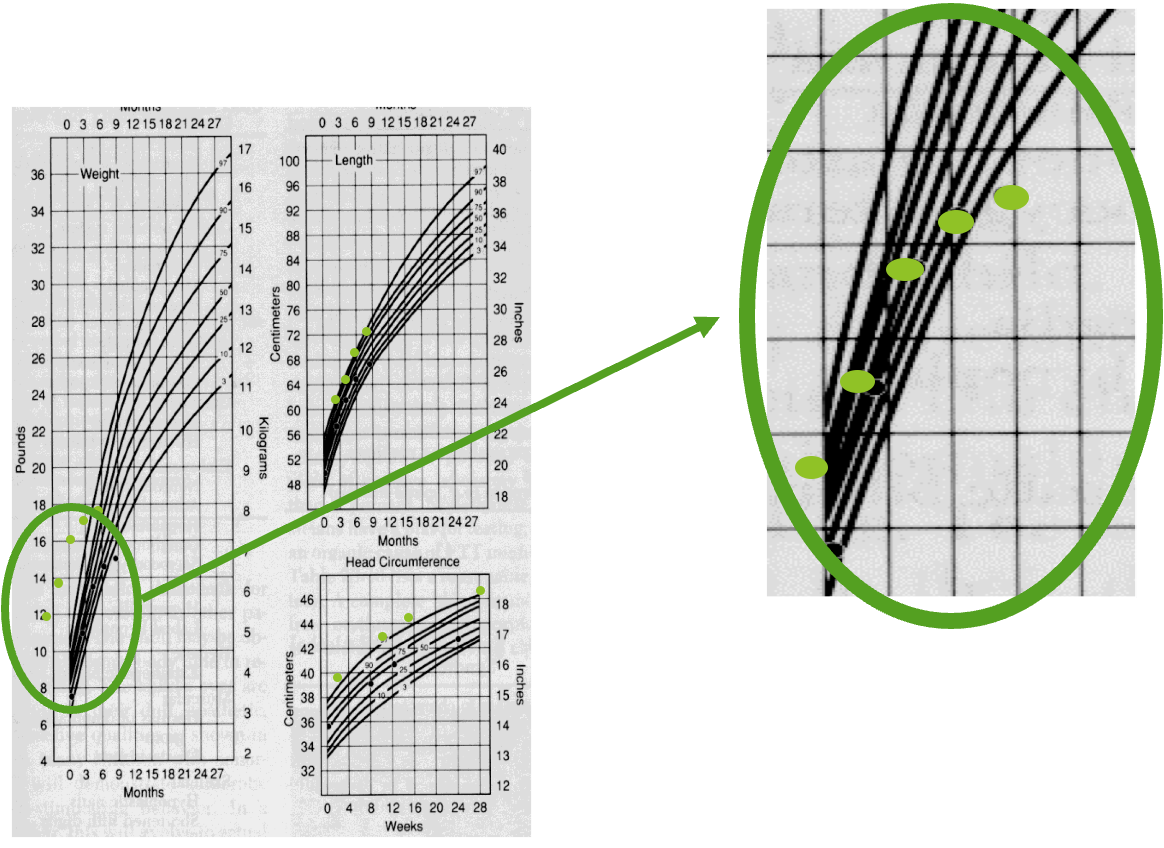

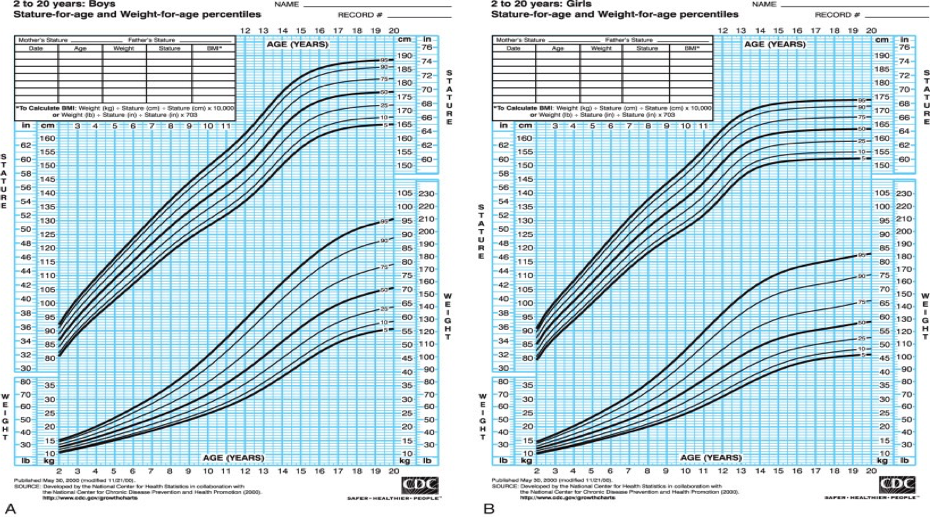

Growth Charts

Short Stature and Growth Failure

- Short stature is usually defined as height >2 standard deviations [SD] below the mean for age.

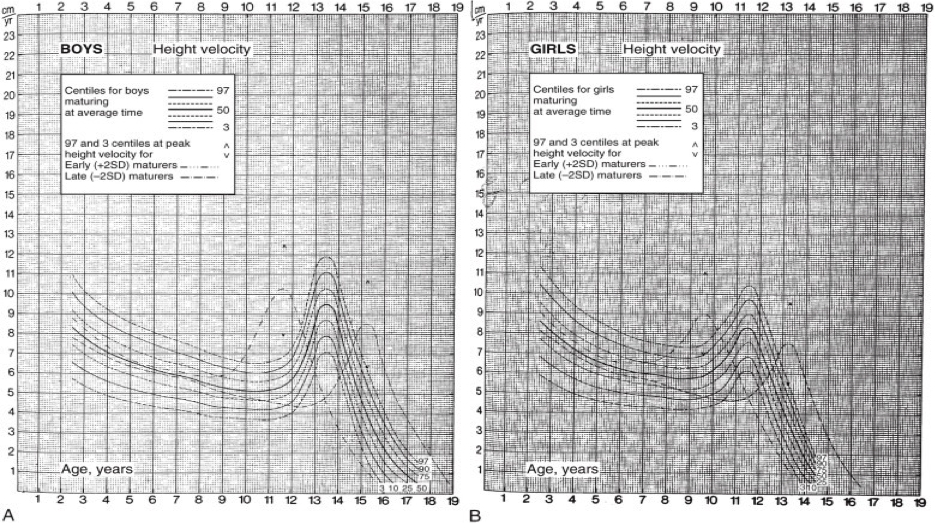

- Growth failure is a subnormal height velocity that leads to a decline in growth percentiles, usually a height velocity >1.5 SD below the mean for age (height velocity below the 25th percentile for age).

- The finding of short stature, particularly if associated with a subnormal height velocity, deserves close attention and appropriate evaluation.

- Tempo - being fast or slow maturing - has to be carefully separated from amplitude - being tall or short. Several characteristic phenomena such as catch-up growth after periods of illness and starvation are largely tempo phenomena, and usually do not affect the amplitude component of growth.

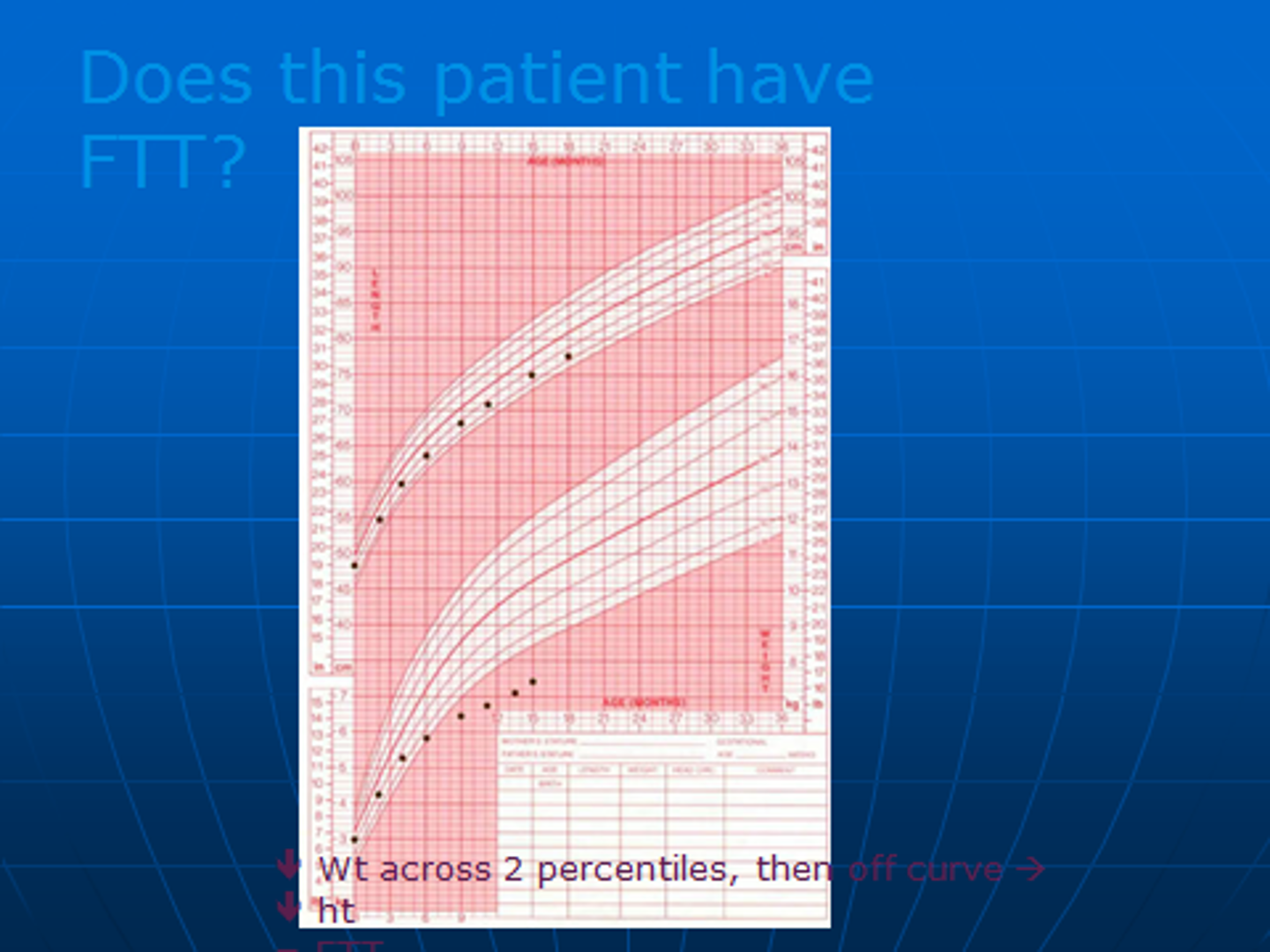

- Failure to thrive refers primarily to poor weight gain in infants and young children (although linear growth may be secondarily affected), whereas short stature refers primarily to subnormal linear growth in childhood and adolescence.

Fetal Growth and Birth Size

- A human being experiences his most rapid linear growth in the prenatal period (growing from near zero to about 50 cm in length in just 9 months). While genetic factors play a major role in postnatal growth, fetal growth and birth size mainly reflect maternal and placental factors.

- Many congenital disorders such as Turner syndrome and congenital GH deficiency that markedly stunt postnatal growth have only minimal effects on prenatal growth and birth size. Therefore, birth size is generally a poor predictor of the eventual growth pattern in most children.

- An exception is the neonate who is small for gestational age (SGA) as a result of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). While most infants with IUGR (caused by nutritional problems or poor placental function) show catch-up growth (a period of rapid growth that occurs spontaneously after relief from the adverse intrauterine condition that had suppressed the rate of growth), 10-20% remain shorter than expected beyond infancy and early childhood, making IUGR one of the possible causes of childhood short stature.

Postnatal Growth Patterns

- Infancy is also a period of relatively rapid growth. Growth then gradually slows as the infant gets older, declining to its lowest point just before puberty, before accelerating again during the pubertal growth spurt, and finally ending with the completion of linear growth about 5 years after the onset of puberty.

- The final height and growth pattern of any given individual are affected by subtle variations in large numbers of many genes.

Growth Velocity at Various Ages

| Age Interval | Average Height Velocity |

|---|---|

| Prenatal | 66 cm/yr |

| 0-1 yr | 25 cm/yr |

| 1-2 yr | 12 cm/yr |

| 2-3 yr | 8 cm/yr |

| 3-5 yr | 7 cm/yr |

| 5–onset of puberty | 5-6 cm/yr |

| Pubertal growth spurt | Girls 8-12 cm, Boys 10-14 cm |

Puberty and Growth in Males

-

In males, testicular enlargement is the 1st sign of puberty and occurs at approximately 11.5 years on average (range, 9-14.3 years).

-

In males with an average tempo of pubertal development, peak growth velocity occurs about 2 years after the onset of puberty (so, later than girls in absolute terms, as well as in terms of the stage of puberty) at approximately 13-14 years, with an average rate of 10.3 cm /yr.

-

It is worth noting that prepubertal males and females grow at very similar rates; the ultimate taller stature of males relative to females is mostly the result of a longer period of growth and a higher peak growth velocity during puberty.

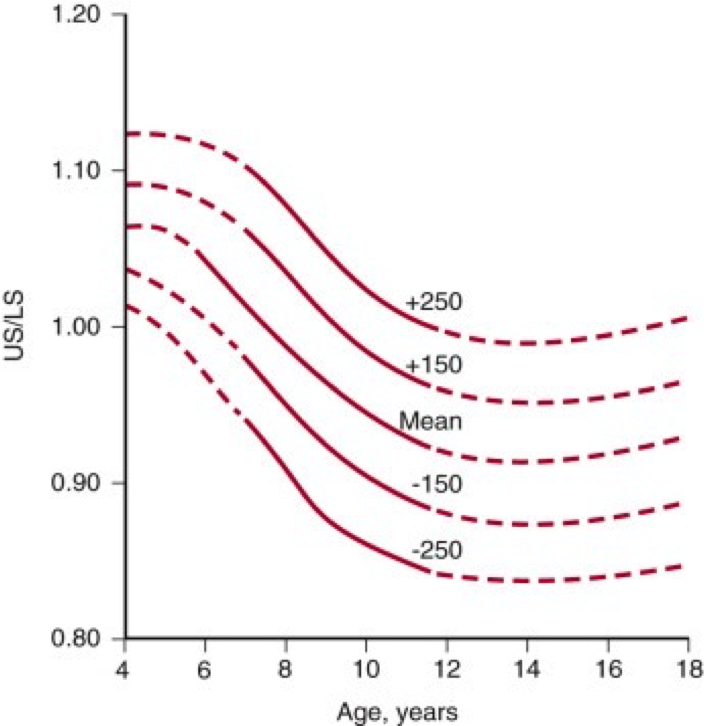

Body Proportions

-

Apart from linear height, it is also useful to assess the upper-to-lower segment ratio (U/L) and the arm span.

-

The U/L is determined by measuring the lower segment (vertical distance between the symphysis pubis and the floor, with the child standing) and the upper segment (the difference between the lower segment and height).

-

Arm span is the distance between the outstretched middle fingertips with the child standing against a flat board or wall.

-

The U/L and arm span are used to determine whether the child is normally proportioned or not.

-

The U/L gradually declines with age throughout childhood. Since infants have relatively short legs, the U/L is high (an average of 1.7) at birth. It then declines throughout childhood as the legs increase in length relative to the upper body, decreasing to a mean of 0.95 by late puberty.

Arm Span and Body Proportions

- The arm span as compared to the height is another measure of body proportions and is normally shorter than the height in younger children and increases to become slightly longer than the height by late puberty (about 5 cm more than height in boys, 1.2 cm more than height in girls).

- Deviations from the norm in the U/L and the arm span may point to conditions such as skeletal dysplasias, Turner syndrome, or long-standing hypothyroidism (increased U/L segment ratio, i.e., relatively short extremities).

- Radiation-induced spinal damage or genetic disorders such as Klinefelter or Marfan syndromes and homocystinuria (low U/L segment ratio, due to a relatively short trunk or unusually long extremities).

Weight in Relation to a Child’s Stature

-

Undernutrition is generally caused by nonendocrine factors (poor nutritional intake, malabsorption, systemic illness) and typically leads to a decrease in weight before a decrease in linear growth.

-

Obesity in childhood is usually exogenous; exogenous obesity is generally associated with an accelerated growth rate.

-

In contrast, endocrine disorders that cause poor growth and short stature are often associated with weight gain and obesity (Cushing syndrome, hypothyroidism, and in some instances, GH deficiency).

-

Therefore, the obese child who has a slow growth velocity is more likely to have an endocrine cause of short stature, while the undernourished child with short stature likely has short stature secondary to poor weight gain and is unlikely to have an endocrine disorder.

Types of Short Stature

- Proportional short stature: Height, weight, and body proportions are reduced uniformly (e.g., due to systemic conditions like malnutrition or chronic illness).

- Disproportional short stature: Discrepancy between trunk and limb lengths (e.g., skeletal dysplasias such as achondroplasia) or Height is affected more than weight.

Causes of Short Stature

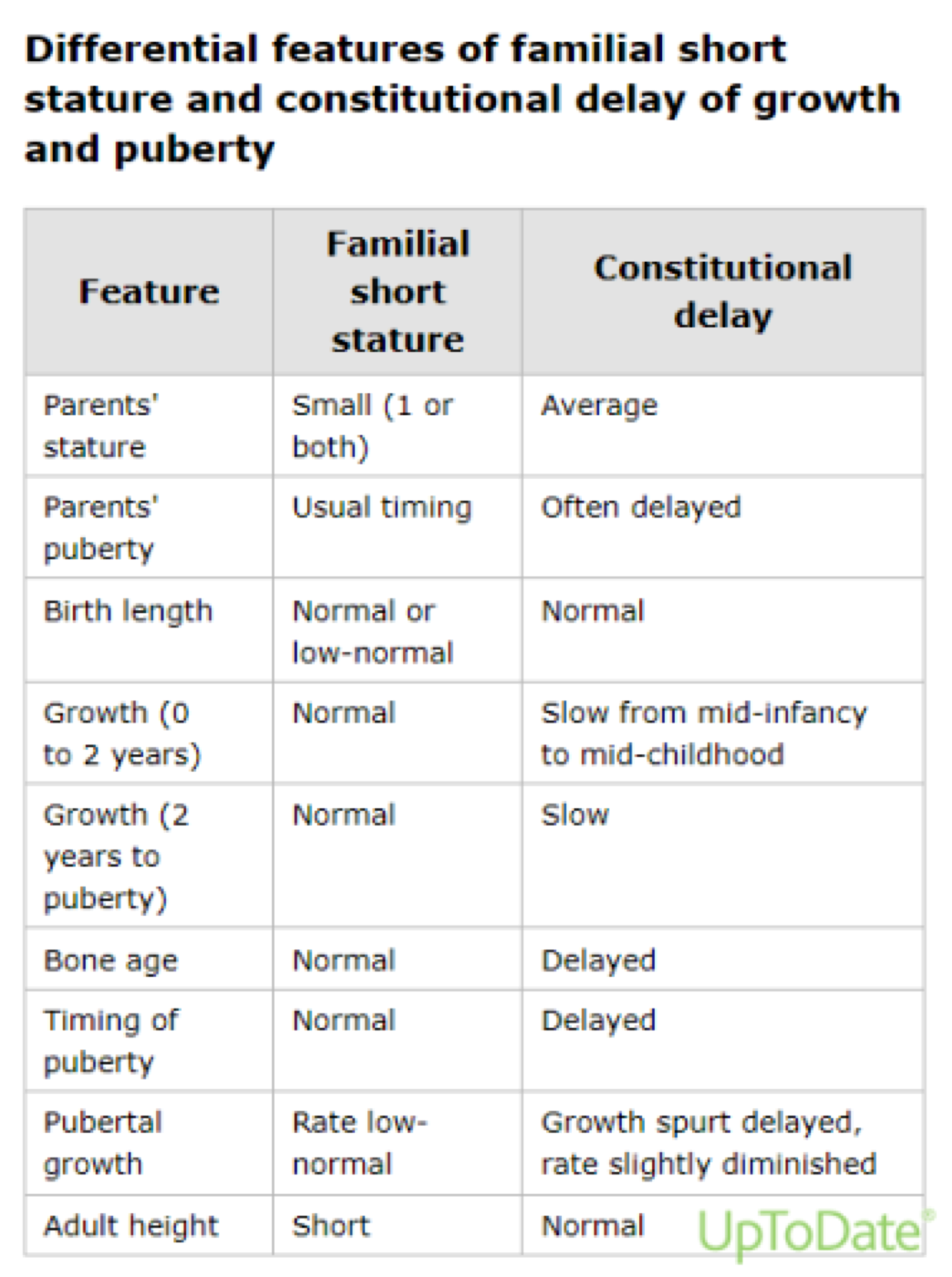

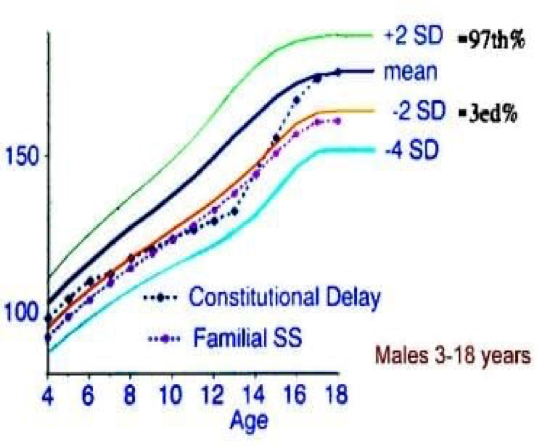

- Physiological:

- Familial short stature.

- Constitutional delay of growth and puberty.

- Pathological:

- Endocrine (e.g., growth hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism).

- Genetic (e.g., Turner syndrome, Achondroplasia).

- Chronic diseases (e.g., celiac disease).

- Nutritional deficiencies.

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): Failure to catch up postnatally.

- Psychosocial factors.

Causes of Short Stature

-

The majority of children with short statures are either normal variants (familial short stature, constitutional delay of growth and puberty) or have no discernible cause (idiopathic short stature [ISS]).

-

A child with growth failure is far more likely to have an underlying pathology than a child who happens to be short but has a normal growth velocity.

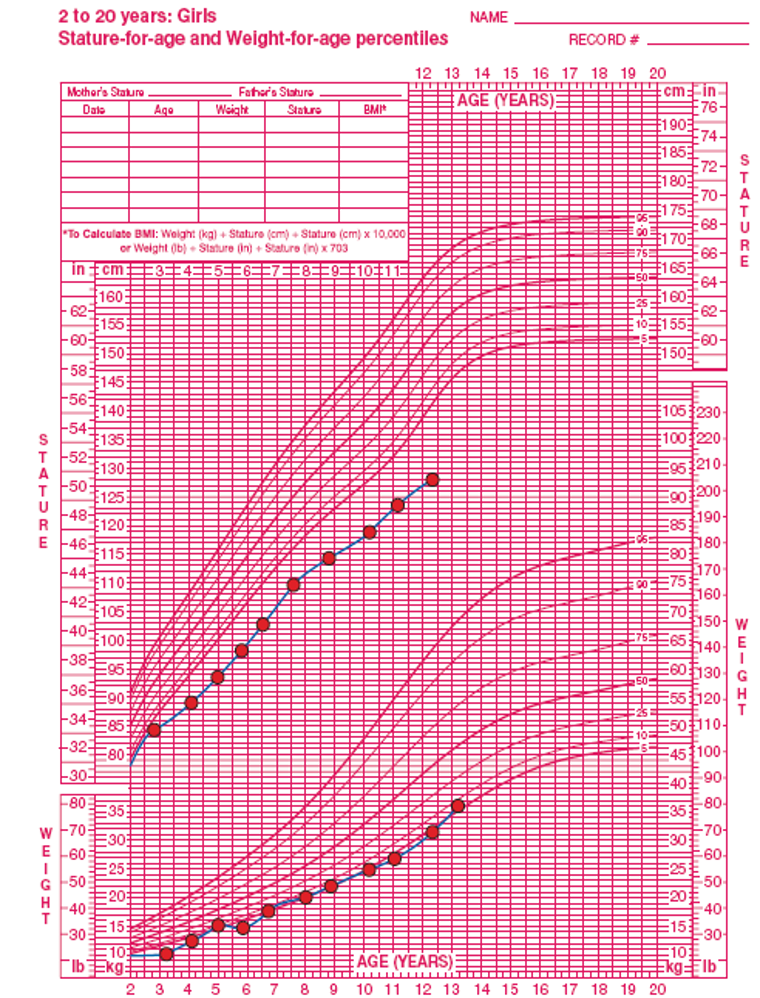

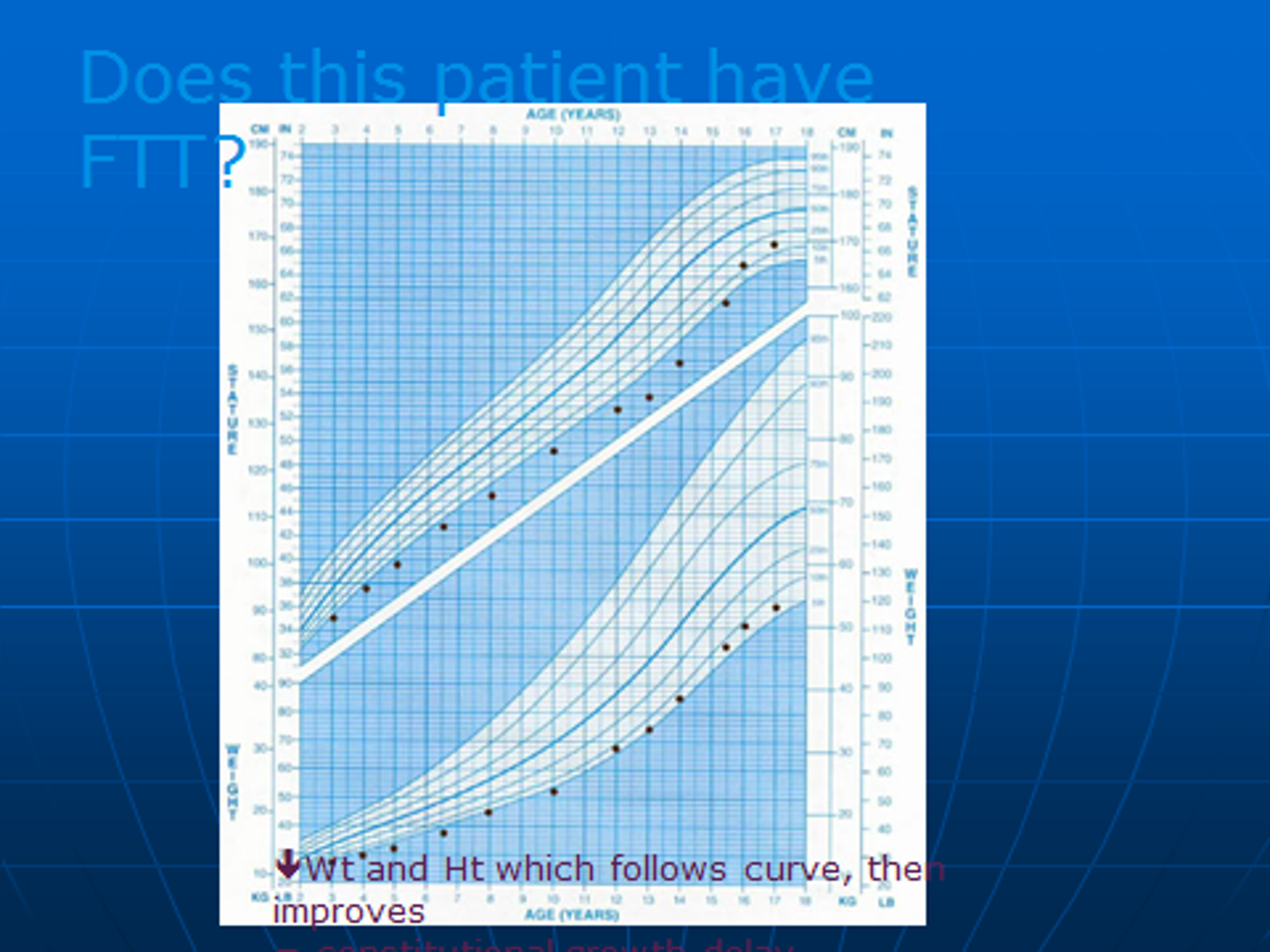

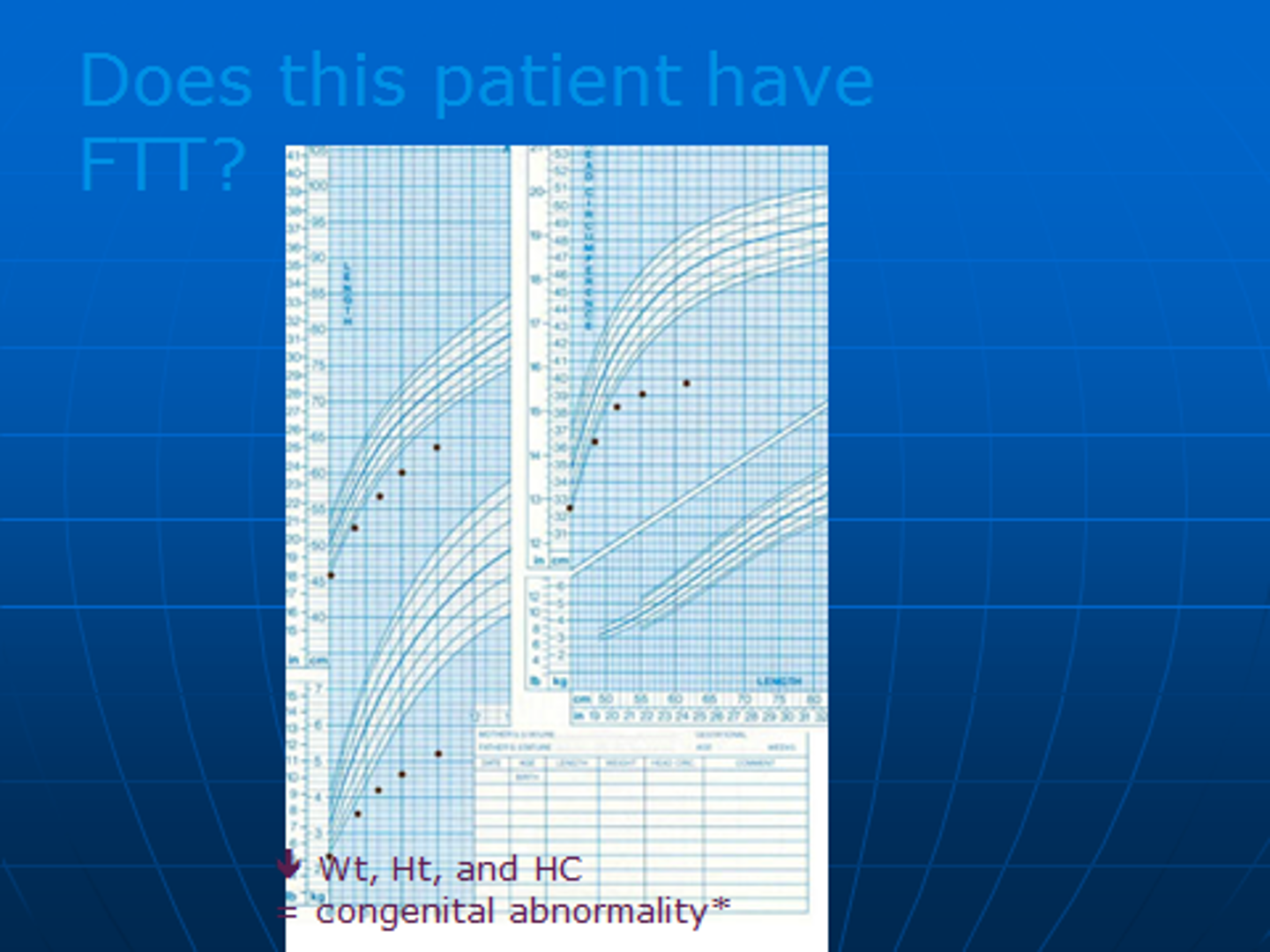

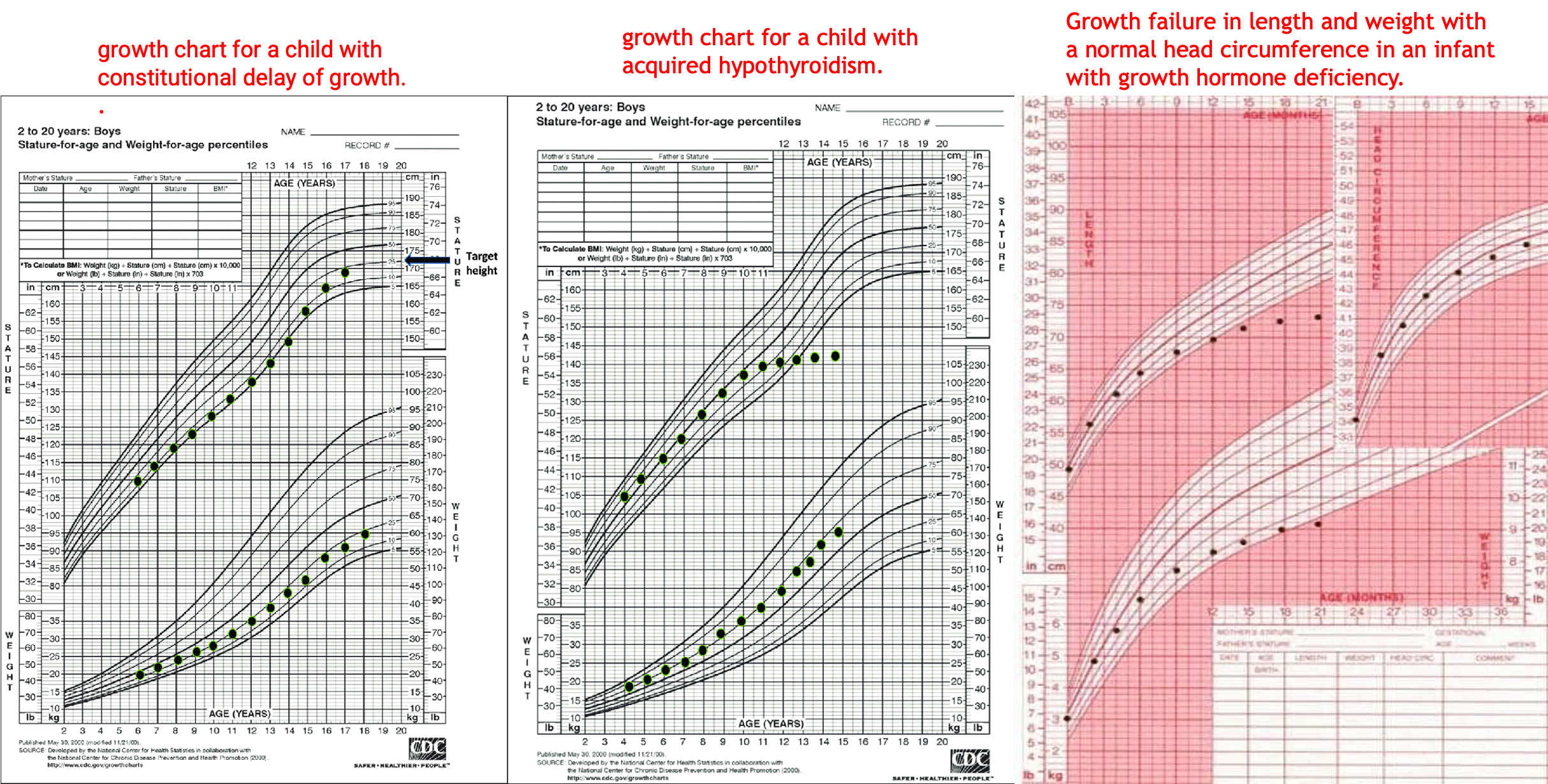

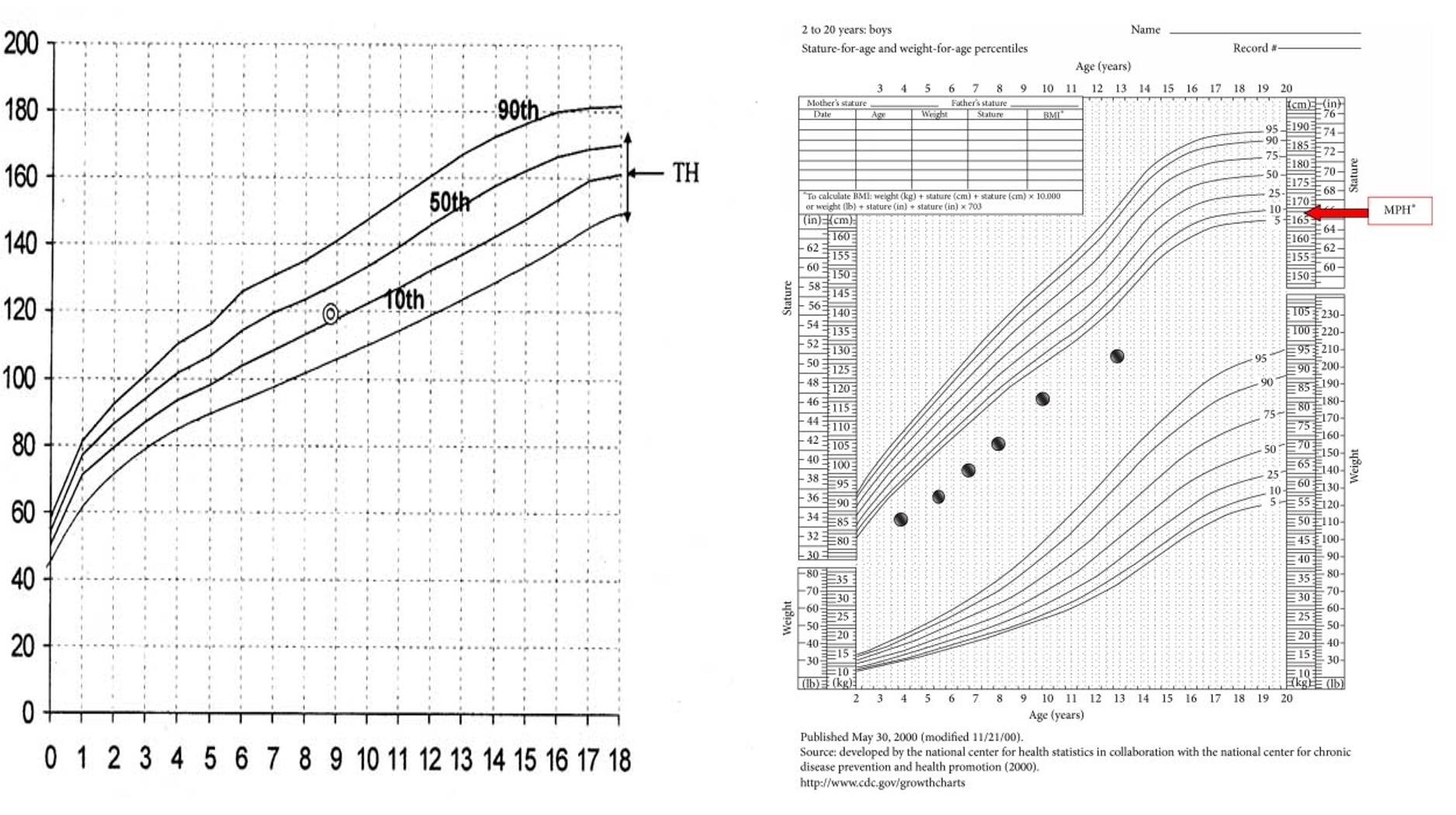

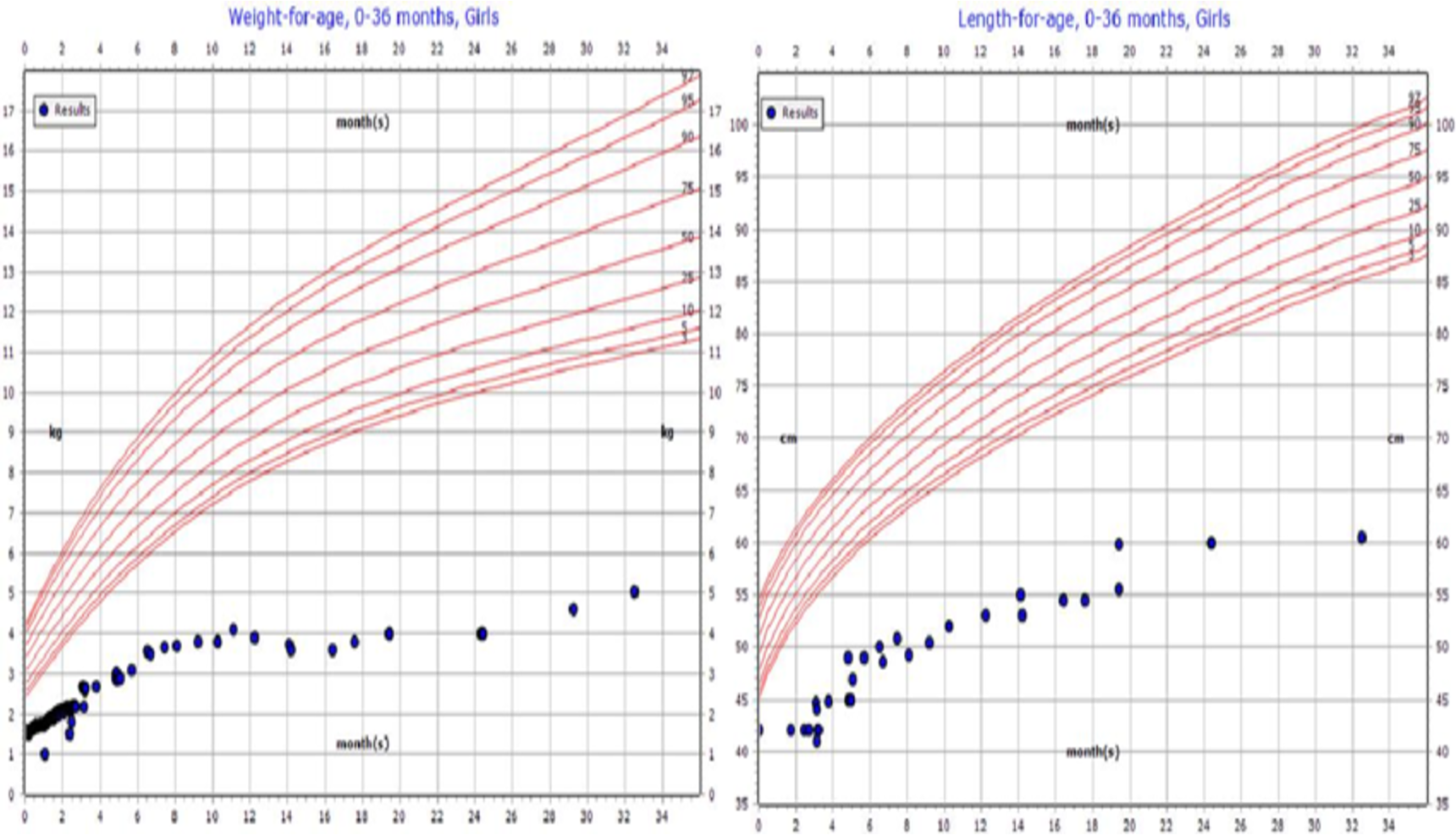

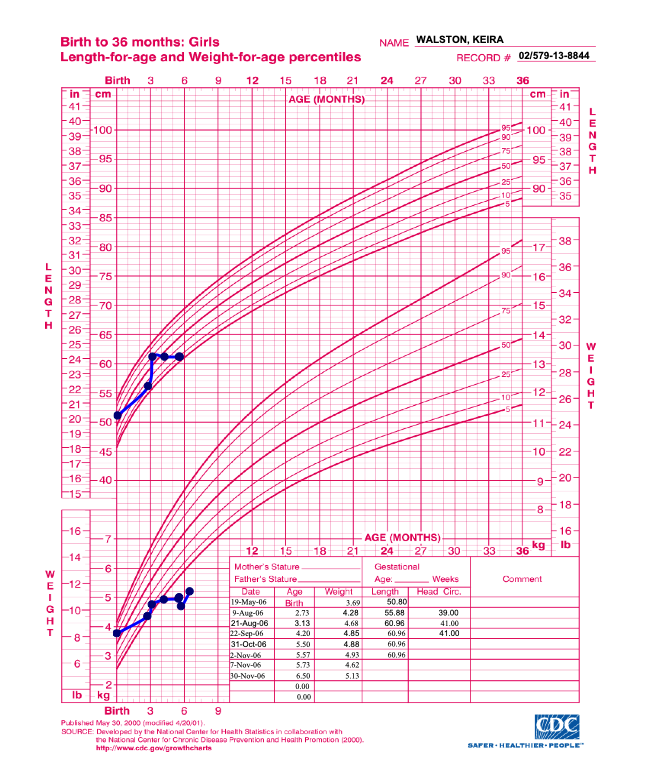

growth chart for a child with constitutional delay of growth. growth chart for a child with acquired hypothyroidism. Growth failure in length and weight with a normal head circumference in an infant with growth hormone deficiency.

Primary and Secondary Growth Abnormalities

I. PRIMARY GROWTH ABNORMALITIES

- Osteochondrodysplasias: Osteogenesis imperfecta, Acromelic dysplasias, rhizo-mesomelic dysplasias, Achondroplasia.

- Chromosomal abnormalities: Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome

II. SECONDARY GROWTH DISORDERS

- Malnutrition

- Chronic disease

- Cardiac: Left-to-right shunts, Congestive heart failure.

- Pulmonary: Cystic fibrosis

- GIT: Inflammatory bowel disease, Celiac disease, Malabsorption, Chronic diarrhea

- Hematologic: Chronic anemia (including sickle cell disease, thalassemias)

- Renal: Chronic renal failure, Renal tubular acidosis

- Immunologic: Congenital immunodeficiency, HIV

- Intrauterine growth restriction

- Endocrine disorders: Hypothyroidism, Cushing syndrome, Pseudohypoparathyroidism, Vitamin D–deficient or –resistant rickets.

IGF Deficiency and Idiopathic Short Stature

III. IGF DEFICIENCY:

- Secondary IGFD.

- GH deficiency due to hypothalamic dysfunction

- GH deficiency due to pituitary GH deficiency

- Primary IGFD (GH insensitivity).

- Primary defects of IGF synthesis

- Primary defects of IGF transport/clearance (ALS)

- Primary GH insensitivity–GH receptor (GHR) defects

- Secondary GH insensitivity (STAT5B)–GHR signal transduction defects

- IGF resistance.

- Defects of the IGF-1 receptor

- Postreceptor defects

IV. IDIOPATHIC SHORT STATURE (ISS)

- Constitutional delay of growth and puberty with normal height prediction.

- ISS with normal bone age and tempo of puberty

Familial and Genetic Factors

- Both parental height and parental pattern of growth are key determinants of a child’s growth pattern.

- The strong familial influence on height is not detectable at birth but is manifested by 2-3 years of age.

- Final adult height is strongly heritable, 80-95%.

- The midparental height (MPH) is used as a measure of the child’s genetic growth potential and is an average of the height of both parents after correcting for sex.

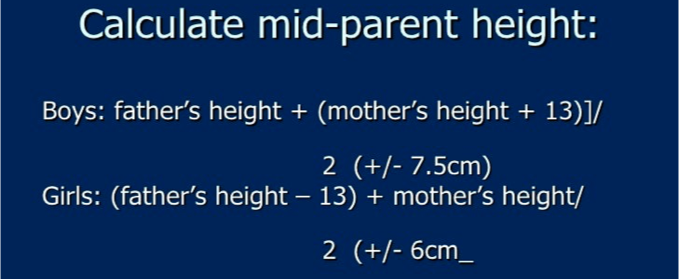

- Thus MPH is determined in the following manner:

- Males: [father’s height in cm + (mother’s height in cm + 13 cm)]/2

- Females: [(father’s height in cm − 13 cm) + mother’s height in cm]/2

- The MPH is a good index of the child’s genetic height potential, but tends to become less accurate if one parent is unusually tall or short.

- In addition to the influence on final adult height, parents’ patterns of growth are also often repeated in their children. In particular, many men with delayed onset of puberty and delayed but normal growth spurts have sons with similar growth patterns.

Case Study

- A 13-year-old boy came with his mother, who complains that he is shorter compared to his classmates. He is 145 cm tall. Mother is 155 cm, Father 174 cm. His bone age is 10 years old. What is his expected height?

- Midparental height: 171 cm

- EXPECTED HT: 163.5-178.5 cm in a range form.

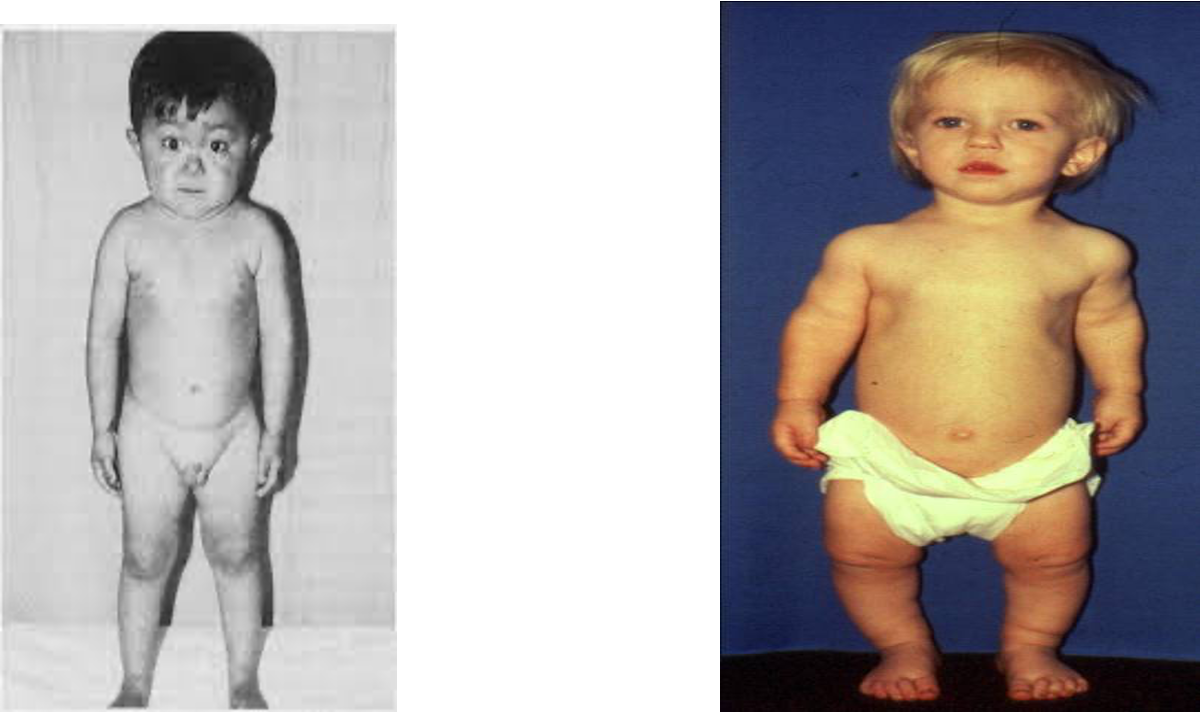

Hypochondroplasia, Acanthosis Nigricans, and Insulin Resistance in a Child

Midparental Height Formulas

- Boys: [father’s height in cm + (mother’s height in cm + 13 cm)]/2

- Girls: [(father’s height in cm – 13 cm) + mother’s height in cm]/2

For both girls and boys, 8.5 cm on either side of this calculated value (target height) represents the likely range for their anticipated adult height (+/- 2 standard deviations).

Ethnic Factors and Secular Trend

- The average height of various populations is not the same; Northern European populations are taller than many other ethnic groups, and it is therefore important to use population-specific standards of growth.

- Two additional observations need to be kept in mind:

- Migrants from countries where the average height is lower tend to have children who are taller than their parents when they move to a country with a higher standard of living. This indicates that at least some of the observed height difference may be environmental (most likely related to nutrition and childhood disease burden) and that this height difference may shrink or disappear in subsequent generations.

- The Northern European populations were themselves much shorter in the 18th and 19th centuries and average heights have steadily increased as living standards improved (reflecting improvements in nutrition and other public health measures). This “secular trend” in height slows down and plateaus over time, but is much more marked in populations that have recently seen an improvement in living standards.

- Thus practitioners should make allowances for ethnic differences in height when evaluating children from different ethnic backgrounds, but should not automatically assume such differences as the sole explanation for short stature in children from historically shorter populations. Growth velocity in particular should not be abnormal even in historically shorter populations, and a subnormal growth velocity should trigger an evaluation in the same way as it would in children from a Northern European background.

General Well-Being

- Short stature may be the presenting feature of such conditions as inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and renal disease.

Psychologic Factors

- Emotional deprivation can lead to very significant growth failure (“deprivation dwarfism” or “psychosocial dwarfism”).

Endocrine Regulation of Growth

- GH is produced by the anterior pituitary under the control of GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) from the hypothalamus, and is essential for normal growth in childhood (small role in prenatal growth). GH is secreted in brief pulses and peak secretion occurs during sleep, so random serum levels have little utility in the evaluation of GH deficiency.

- GH stimulates the production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (primarily in the liver, but also in some target tissues). GH also has direct actions on bone. Most circulating IGF-1 is bound to IGF-binding proteins. Because IGF-1 levels in the blood are stable throughout the day and reflect the integrated effect of GH secretion, measurement of IGF-1 is often used as a surrogate measure of GH secretion.

- Thyroid hormone: limited role in prenatal growth, essential for normal postnatal linear growth, both via direct actions on the epiphyseal growth plate and via a permissive effect on GH secretion. Hypothyroidism can therefore lead to very profound growth failure.

Glucocorticoids and Sex Steroids

- Glucocorticoids do not play any significant role in promoting growth, but are powerful inhibitors of growth when present in excess. Persistent exposure to excess corticosteroids leads to severe growth failure along with weight gain. Deficiency of glucocorticoids does not adversely affect growth.

- Sex steroids mediate the pubertal growth spurt. This involves direct effects of sex steroids on bone growth as well as steroid-induced amplification of GH secretion. The bone-maturing action of sex steroids is mediated by estrogen in both sexes; while testosterone has some direct effects on bone strength and thickness, most of the effects of testosterone on linear growth and the maturation of growth plates in males occur via the action of estrogen produced by the peripheral conversion of testosterone. Consequently, even in males, bone maturation can be affected by genetic defects in the production or action of estrogen.

- Sexual precocity (true precocious puberty, exogenous exposure, or congenital adrenal hyperplasia) tends to accelerate linear growth transiently as a result of premature or excessive production of sex steroids. But if left untreated, these conditions advance osseous maturation, leading to premature epiphyseal fusion and a short final adult height.

- The absence of sex steroids (hypogonadism) in the absence of other abnormalities blunts the pubertal growth spurt, but tends not to limit final height, as bone maturation and epiphyseal fusion are also delayed by the lack of estrogen in these patients.

Bone Age

-

Radiograph of the nondominant hand can be used to assess bone age (i.e., the degree of maturation of the bones compared to age-matched standards).

-

Bone age is usually estimated by comparing the child’s radiologic findings with a standard set of radiologic images.

-

Bone age is very closely correlated with pubertal maturation and an assessment of bone age can be especially useful in cases of precocious puberty, delayed puberty, and constitutional growth delay.

-

Except in cases of precocious puberty, bone age is rarely useful in the evaluation of short stature in a child less than 5 years of age.

Presentation

-

Growth Concerns:

- Height consistently below the 3rd percentile for age and sex on growth charts.

- Growth velocity slower than expected for age (crossing percentiles downward).

-

Associated Features:

- Proportional short stature: Height, weight, and body proportions are reduced uniformly (e.g., due to systemic conditions like malnutrition or chronic illness).

- Disproportional short stature: Discrepancy between trunk and limb lengths (e.g., skeletal dysplasias such as achondroplasia).

-

Delayed Development:

- Delayed puberty or bone age compared to chronological age.

- Delayed motor or cognitive milestones if associated with syndromic causes.

-

Facial or Physical Features (syndrome-specific):

- Features such as a webbed neck, low-set ears, or wide-spaced eyes in Turner syndrome.

- Characteristic facial features in genetic syndromes like Noonan or Down syndrome.

-

Other Symptoms:

- Signs of chronic disease: fatigue, frequent infections, or poor appetite.

- Hormonal imbalances: symptoms of hypothyroidism (e.g., cold intolerance, dry skin) or growth hormone deficiency.

-

Psychosocial Impact:

- Concerns about appearance, self-esteem issues, or bullying.

Diagnostic Approach: History

- Growth history: Birth weight, length, and growth pattern since birth.

- Family history: Parental heights, age of puberty onset in family members (familial short stature or constitutional delay).

- Nutritional history: Diet adequacy and signs of malnutrition.

- Systemic symptoms: Signs of chronic illness (e.g., diarrhea for celiac disease, fatigue for hypothyroidism).

- Developmental milestones: Delays indicating syndromic or neurological issues.

- Pregnancy and birth history: Preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or perinatal complications.

Diagnostic Approach: Physical Examination

-

Anthropometry:

- Measure height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and compare with growth charts.

- Calculate mid-parental height (for expected genetic potential).

-

Proportions:

- Assess upper-to-lower segment ratio and arm span.

- Disproportionality suggests skeletal dysplasia.

-

Syndromic features: Examine for dysmorphic features (e.g., webbed neck in Turner syndrome).

-

Pubertal assessment: Tanner staging to assess pubertal development.

-

Growth Chart Analysis:

- Plot height, weight, and head circumference.

- Assess growth velocity (falling off percentiles indicates pathological short stature).

Diagnostic Approach: Investigation

Basic Tests (screen for common causes):

- Complete blood count (CBC): Check for anemia or signs of chronic disease.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP): Inflammation markers.

- Thyroid function tests (TSH, free T4): Rule out hypothyroidism.

- Tissue transglutaminase antibody (tTG-IgA): Screen for celiac disease.

- Liver and kidney function tests.

- Bone age X-ray: Compare skeletal maturity to chronological age.

Diagnostic Approach: Investigation…cont

Specific Tests (based on suspicion):

-

Growth hormone deficiency:

- Serum insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3).

- Growth hormone stimulation test (e.g., clonidine or arginine stimulation).

-

Genetic testing: Karyotype for Turner syndrome, or specific genetic panels for suspected syndromes (e.g., Noonan syndrome).

-

Other hormone tests: Cortisol levels (Cushing syndrome), gonadotropins (LH, FSH for delayed puberty).

-

Skeletal survey: For suspected skeletal dysplasia.

Management of Short Stature

-

Address Underlying Cause:

- Treat hypothyroidism with levothyroxine.

- Initiate a gluten-free diet for celiac disease.

- Manage chronic illnesses (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease).

-

Growth Hormone Therapy indicated in:

- Growth hormone deficiency.

- Turner syndrome.

- Prader-Willi syndrome.

- Chronic kidney disease.

- Small for gestational age (SGA) without catch-up growth by age 2-4 years.

- Administered as daily subcutaneous injections under endocrine supervision.

-

Nutritional Support:

- Provide a balanced diet addressing any deficiencies (e.g., protein, vitamins, and minerals).

-

Psychosocial Support:

- Counseling for the child and family to address psychological impact and build self-esteem.

-

Monitor Growth:

- Regular follow-up to track height, weight, and pubertal progress.

-

Referral to Specialists:

- Endocrinologist: For growth hormone assessment and hormonal causes.

- Geneticist: For evaluation of syndromic features or family history of genetic conditions.

- Gastroenterologist: If celiac disease or malabsorption is suspected.

- Orthopedic specialist: For skeletal anomalies.

Prognosis

- Dependent on:

- Underlying cause.

- Timing and adequacy of treatment.

- Early diagnosis improves outcomes.

Summary of key points:

- Differentiate physiological vs. pathological causes.

- Early diagnosis and treatment are critical.

- Support growth and overall well-being.

Sunjet sakatti

Growth charts of an 8 month old boy with Non-organic FTT