GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Review the patient’s record and confirm the identity of the patient & others in the room.

An appropriate distance should be maintained during the history-taking portion.

The examiner should wash hands thoroughly before & after the examination.

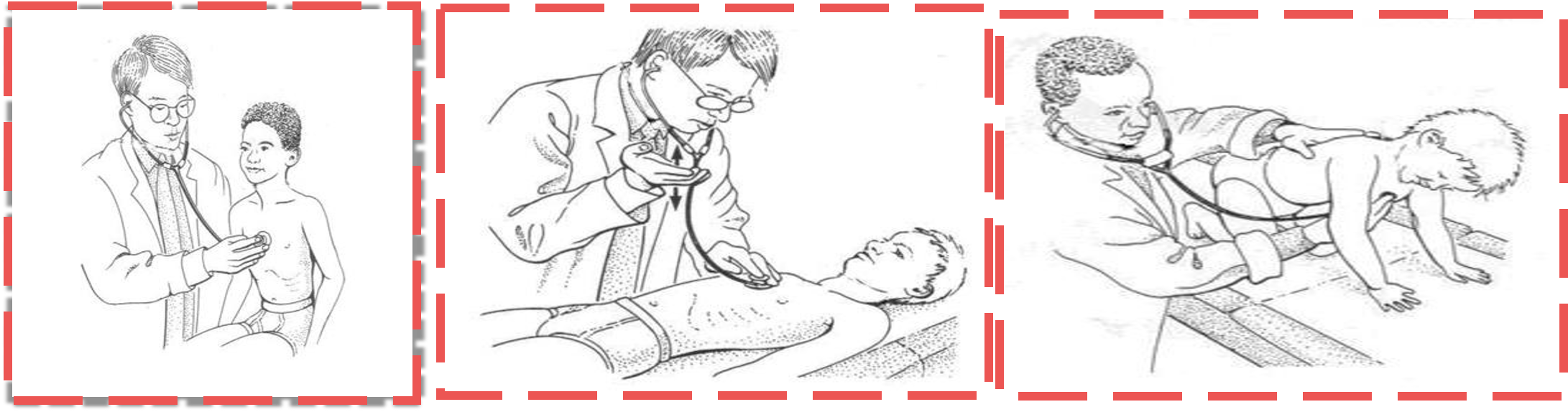

Infants younger than six months who have no stranger anxiety and children older than 36 months who are familiar with the examining clinician generally cooperate during the examination without being held by their caregiver.

Physical examination of 5- to 12-year-old children usually is easy to perform because these children are not typically apprehensive and tend to be cooperative.

Physical examination

-

Gain paediatric patient cooperation (toys, distracting objects, and pictures). Chewable snacks or liquid refreshments can be used.

-

If a child >4 years old fails to cooperate for an examination, even in the presence of a caregiver, it may be due to an earlier traumatic encounter between the patient and another examiner, a failure on the part of the current examining clinician to use the correct approach, or an underlying psychosocial problem.

-

For patients old enough to understand but who appear apprehensive, the examiner should explain what is going to be done during the examination and allow them to look at and touch any of the instruments to be used. Older patients should be warned in advance of potential pain or discomfort.

-

A nurse should be present, and parents are asked to leave for the examination of the anorectal, genital areas or breasts, or examination of suspected child abuse.

-

Patient privacy should be respected. If a patient objects to being unclothed, allow him or her to remain clothed until a specific part of the anatomy must be checked. The patient should be asked to remove or pull free the garments that are hindering visualization, palpation, or auscultation.

-

For an infant, begin by examining the eyes, noting the red-light reflex, extraocular eye muscle movements, and visual tracking, and then move to other parts of the body or organ systems before finally performing the often sensitive ear examination.

-

For the older child, the examination begins at the head and progresses down the body, with the neurologic examination performed last.

-

In general, the portions of the examination that require the most patient cooperation, such as BP measurement, lung and heart auscultation, and eye and neurologic examinations, are performed initially. These are followed by the more bothersome portions, including abdominal and ear examinations and measurement of head circumference.

-

If the patient has a localized complaint, sign, or symptom, that part of the examination should be performed last. As an example, if right-lower-quadrant abdominal pain is thought to be attributable to appendicitis, by not examining that part of the body first, the clinician may be able to divert the patient’s attention away from the involved area and rule out other possible causes for the pain.

PEDIATRICS PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

-

IMPORTANT HINTS:

- Avoid irritating the child and prevent him from crying (if possible).

- Examine the child in the most comfortable way according to his age (exam table, mother’s hands, mother’s lap, while playing with a toy, while nursing…).

- Postpone the painful and/or irritating examination (temp/throat/ears).

-

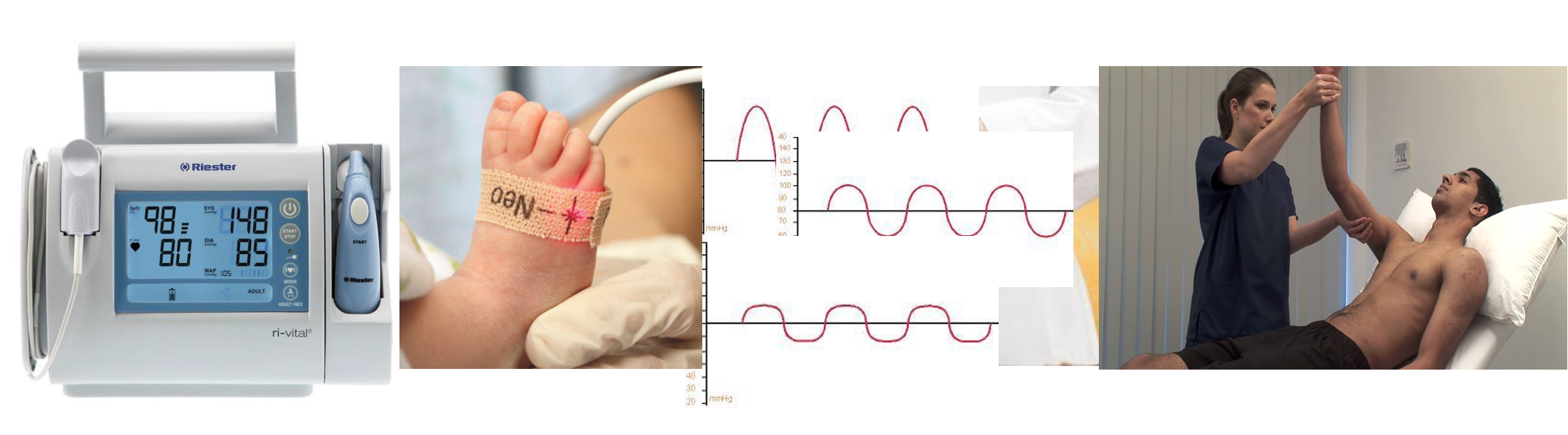

Vital signs

- Temperature

- Heart Rate

- Respiratory Rate

- Blood Pressure

- O2 Saturation

- CR time

-

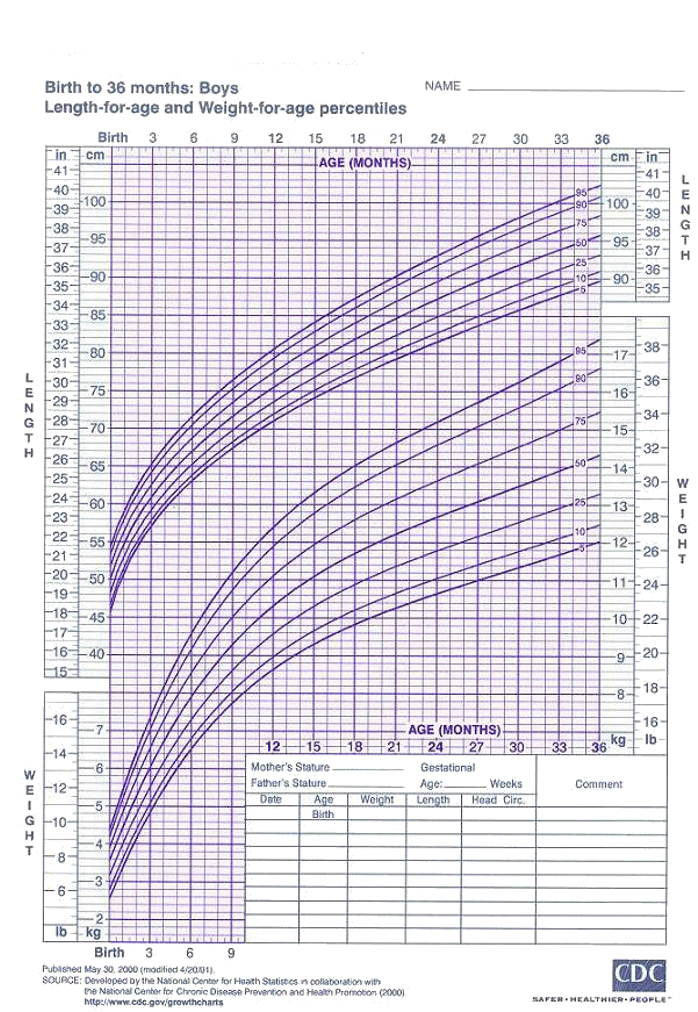

Measurements (Wt, Ht, HC)

- Always use growth charts and indicate the percentiles.

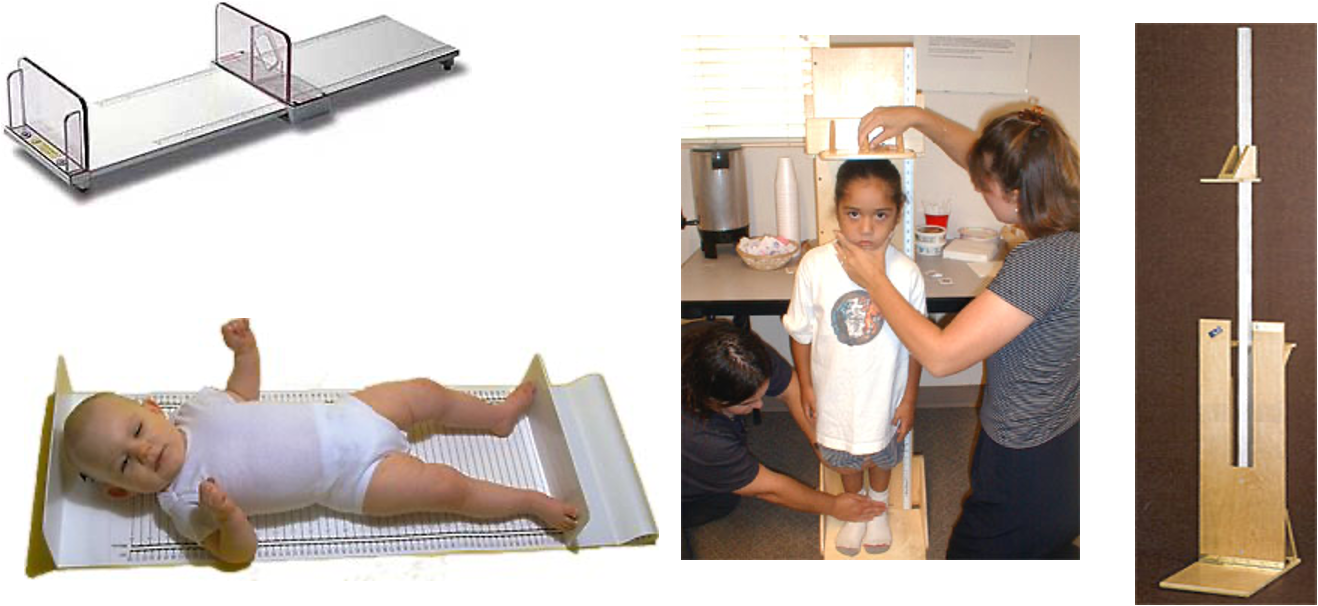

- Use an appropriate scale for age to measure the weight.

- Naked weight (when possible).

- Measure recumbent length till 2 years of age and then standing length (height) after that.

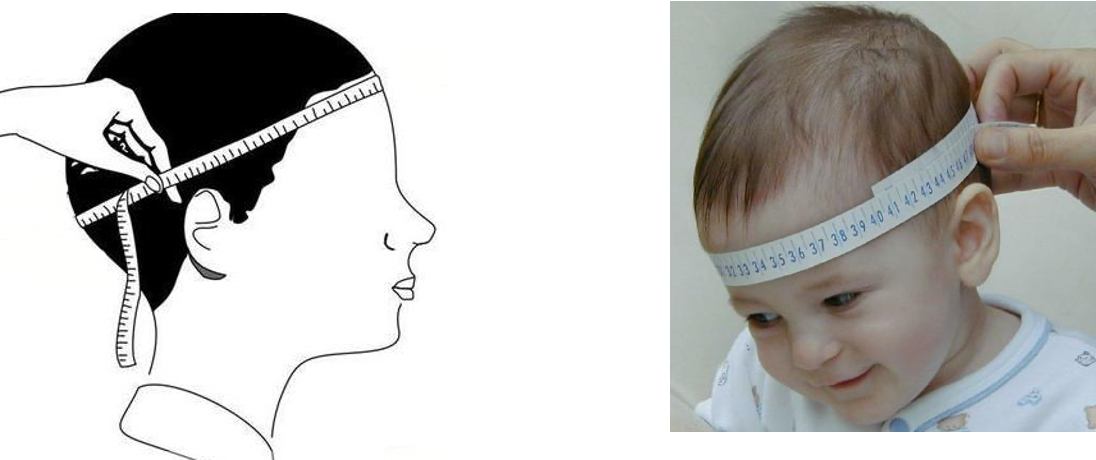

- HC is the occipitofrontal circumference and measures the circumference passing through the most distal points on the occiput and the frontal area.

Stadiometers for Measuring Children and Adolescents

- General Appearance The examiner may gain significant insight into important social and family dynamics by observation alone when entering the patient’s room:

- State of alertness/level of consciousness

- Degree of comfort (calm, nervous, shy)/Awareness to environment

- State of well-being (normal, ill-appearing, distressed)/Facial expression

- Activity level (sedate, alert, active, fidgety)

- Physical appearance (neat, disheveled, unkempt)

- Behavior and attitude (happy, sad, irritable, combative)

- Body habitus (overweight, underweight, short, tall) and nutritional status (malnourished, normal, corpulent)

- Any special decubitus

| Observation | Indicators | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Possibility of Neglect | No eye contact, lack of animation, absence of social smile | Potential neglect of the child by the caregiver |

| Child appears ill | Lies completely still, verbally responsive, noticeable position changes | Possible acute abdomen |

| Dyspneic Patient | Sitting upright, slightly forward, arms extended, hands resting on knees | Possible exacerbation of asthma |

| Crying Infant | Pitch and intensity of the cry | - Boisterous, hardy cry: somewhat reassuring - Weak, listless cry: may indicate serious illness |

| High-Pitched Cry | High-pitched cry | Could indicate increased intracranial pressure, painful injury, toxic reaction, strangulated inguinal hernia, or other serious disorders |

| Breathing Pattern and Skin Color | Rapid, shallow respiration, no acute distress | Underlying cause could be primary pulmonary disease or respiratory compensation for metabolic acidosis |

| Developmental Status Evaluation The examiner should evaluate the developmental status before touching the child:| | Motor function, interaction with objects and people, response to sounds, speech pattern | Clues about normal development or need for extensive developmental assessment |

-

Skin, Hair, and nails:

- Skin: Color, elasticity, texture, rash

- Hair: Texture, color, distribution, areas of hair loss

- Nails: Color, texture, shape

-

Head and neck

- Head: Size, shape, fontanelles, sutures, craniotabes

- Face: Shape, complexion (pallor, cyanosis, jaundice), edema

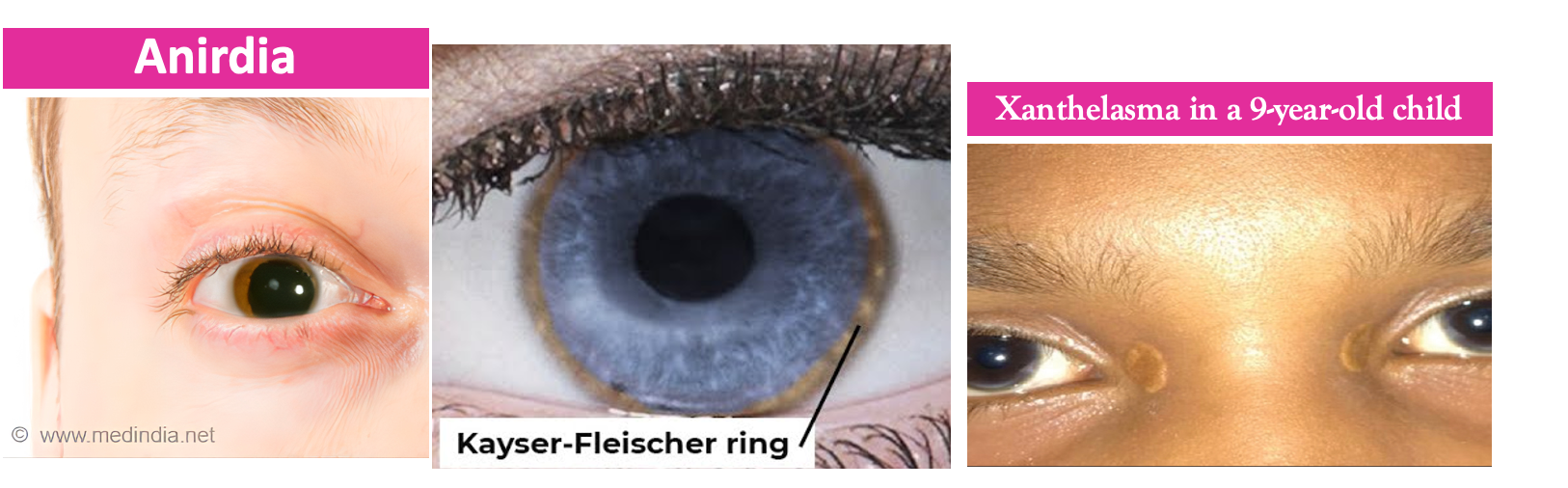

- Eyes: Degree of slanting, sclera, eyelids, spacing, epicanthal folds, palpebral fissure, eyelashes, squint, sunken, sunset

- Ears: Size, position, deformity, discharge, external canal & tympanic membranes (shape, color, position, light reflex)

- Mouth: Mandible, size, lips, tongue, gum, teeth, palate, throat and uvula

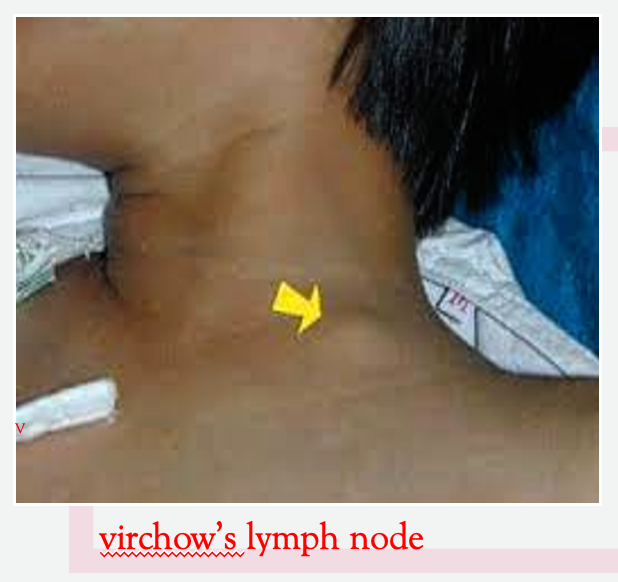

- Neck: Length, pulsations, thyroid, webbing, lymph nodes, torticollis

-

Lymph nodes:

- Examine all groups (occipital, cervical, axillary, groin)

- Size, consistency, matting, attachment to skin, tenderness

-

Lungs and thorax (inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation)

-

Heart (inspection, palpation, auscultation)

-

Abdomen and genitalia: (inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation). Examine for ascites.

-

Back and spine (inspection and palpation)

-

Extremities (musculoskeletal, joints, and peripheral vessels)

-

Neurological and psychiatric

CVS EXAMINATION

(Image Placeholder)

Examination

- General appearance: higher functions, distress, cyanosis, pallor, clubbing, dysmorphic features, activity, monitors, lines, reaction, parents’ attitude…

- Growth chart:

- Vital signs:

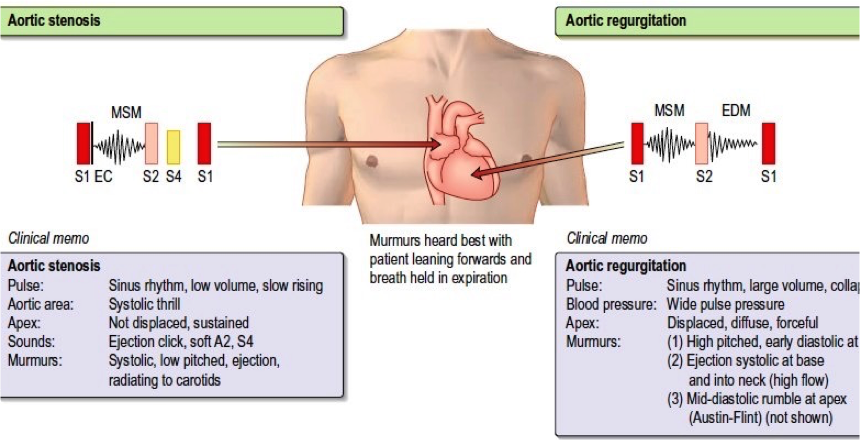

- Pulse: All four limbs

- Blood pressure: All four limbs

- Pulse Oxymetry:

- Pulses: Pulses are the result of the difference between systolic and diastolic status of the vasculature. An increase in the difference between systole and diastole results in a more pronounced pulse.

Examine for a collapsing pulse by placing your fingers across the anterior aspect of the patient’s forearm and applying just enough pressure to occlude the radial pulse.

Confirm that the patient has no pain in their shoulder, and then elevate their arm above their head whilst maintaining the position of your hand.

You are feeling for a forceful knocking sensation that is typical of aortic regurgitation, commonly known as the ‘collapsing’ or ‘water-hammer’ pulse.

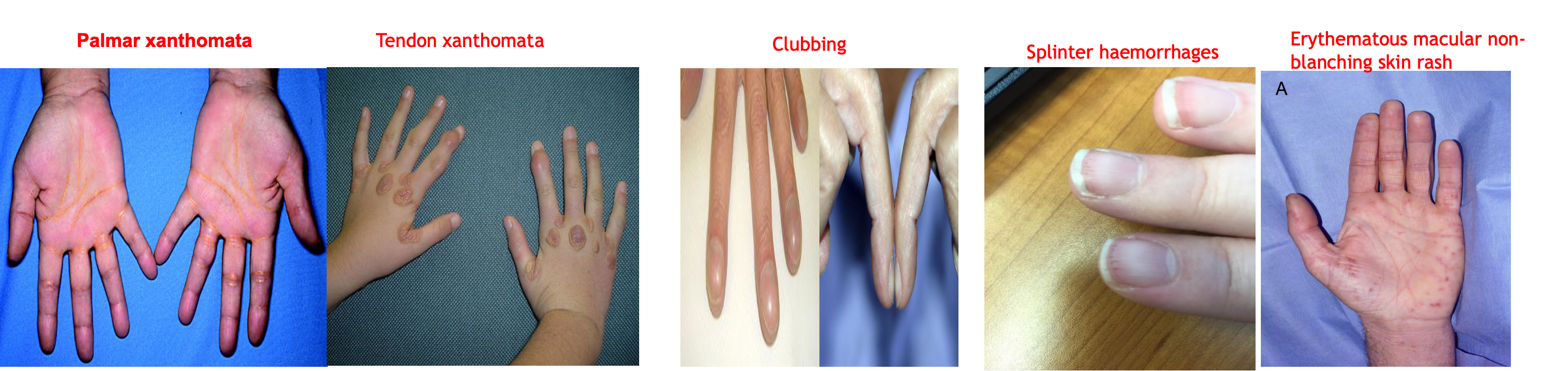

- Hands Inspect:

-

Temperature

-

Capillary refill (at level of heart)

-

Colour (peripheral cyanosis)

-

Clubbing – perform Shamroth’s window test and consider cardiac causes (congenital cyanotic heart disease; endocarditis)

-

Blood glucose testing on fingertips

-

Tendon xanthomata (hyperlipidaemia)

-

Clubbing: This is enlargement of the tips of digits caused by hypoxia to peripheral tissue due to poor cardiac output and/or cyanosis. Peripheral tissues compensate by forming more capillaries to improve oxygenation, which results in swelling of the peripheries of digits.

-

- Tendon xanthomata,

- Palmar xanthomata,

- Janeway lesions (endocarditis),

- Osler nodes (endocarditis),

- Splinter haemorrhages (trauma, vasculitis, endocarditis),

- Pale palmar creases (anaemia),

- Palmar erythema (Hyperthyroidism; polycythaemia)

- Arachnodactyly (Marfan’s syndrome)

- Erythematous macular non-blanching skin rash

- Splinter haemorrhages

Formulas and General Rules - Rough Approximations

-

Pulse or Heart Rate (HR):

- Infant Pulse: 160

- Preschool Pulse: 120

- Adolescent Pulse: 100

-

Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP):

- Infant SBP: 80

- Preschool SBP: 90

- Adolescent SBP: 100

-

Respiratory Rate (RR):

- Infant RR: 40

- Preschool RR: 30

- Adolescent RR: 20

-

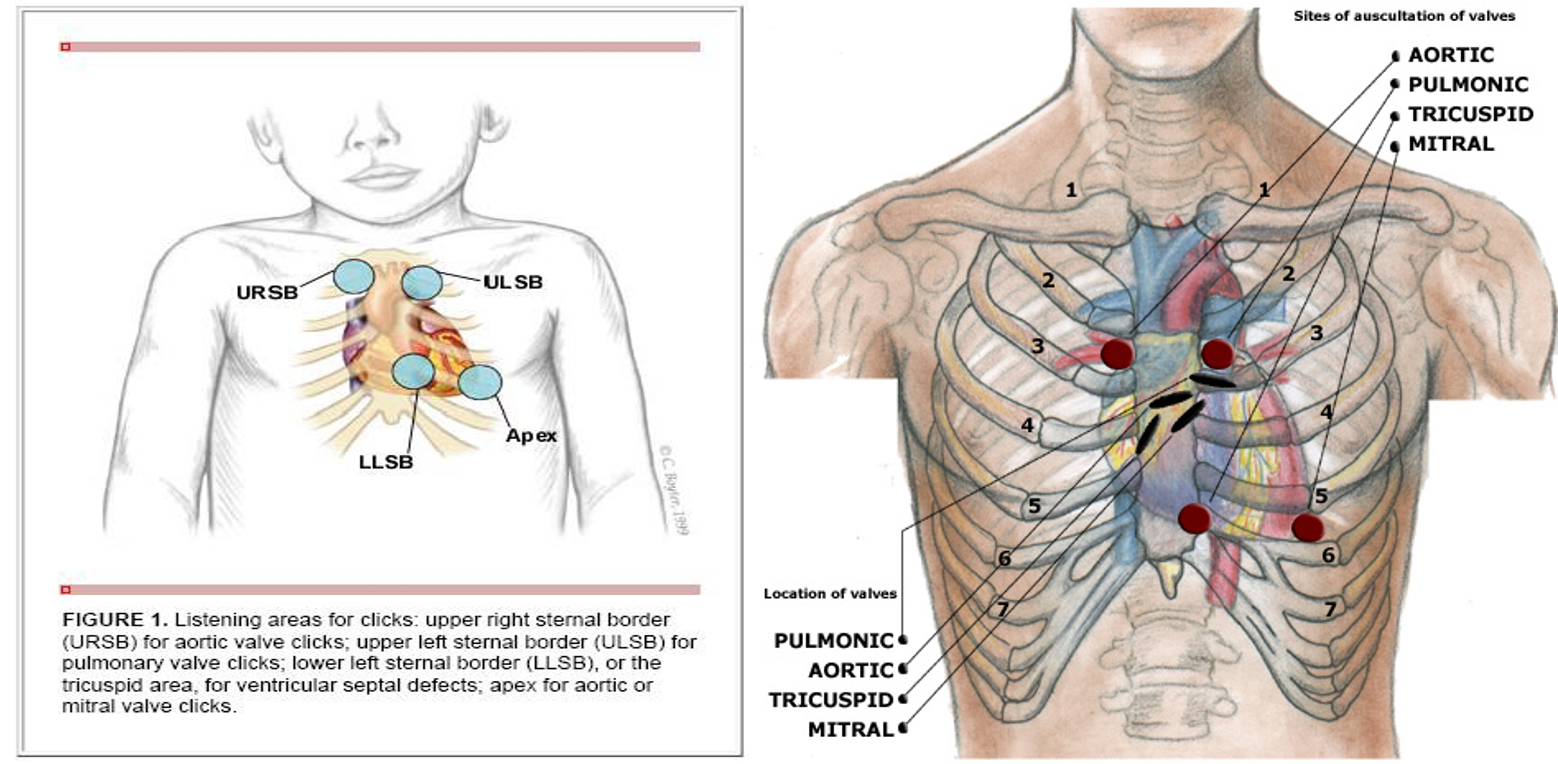

Cardiovascular:

- Inspection

- Palpation

- Percussion?

- Auscultation

- 1st and 2nd heart sounds

- 3rd (gallop) and 4th

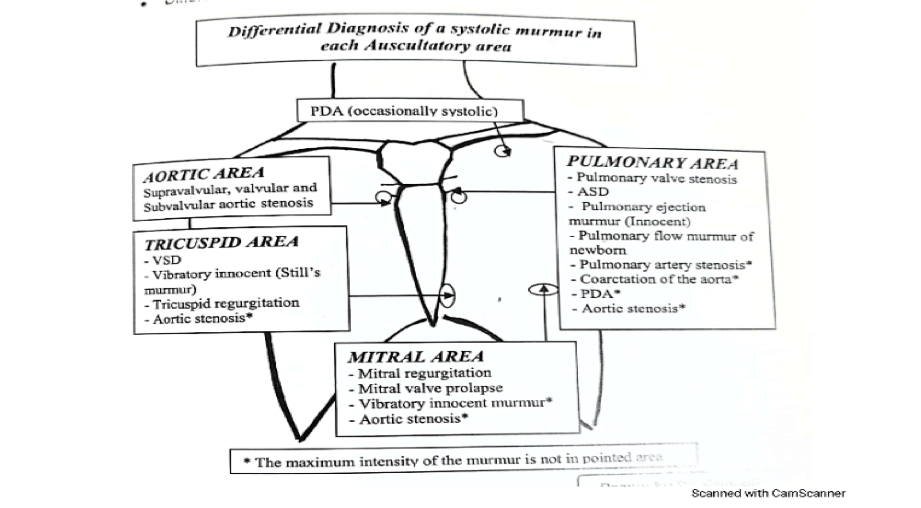

- Murmur: site, phase, duration, radiation, intensity, grade

- Clicks

- Bruit: liver, renal, brain

Assess tracheal position. Gently assess the position of the trachea, which should be central in healthy individuals:

- Ensure the patient’s neck musculature is relaxed by asking them to position their chin slightly downwards.

- Dip your index finger into the thorax beside the trachea.

- Gently apply side pressure to locate the border of the trachea.

- Compare this space to the other side of the trachea using the same process.

- A difference in the amount of space between the sides suggests the presence of tracheal deviation.

Causes of tracheal deviation:

- Away: Tension pneumothorax and large pleural effusions.

- Towards: Lobar collapse and pneumonectomy.

Palpation of the trachea can be uncomfortable, so warn the patient and apply a gentle technique.

Palpate

-

Apex beat:

- Normal: 5th intercostal space, mid-clavicular line

- Forceful: LVH, aortic stenosis

- Heaving/thrusting: aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation

- Tapping: mitral stenosis

- Double: HOCM

-

LV and RV heave (ventricular hypertrophy)

-

Thrills (palpable murmur)

-

Maneuvers with auscultation:

- Supine, sitting and standing: Increase pre-load in supine, exaggerating flow murmurs.

- Valsalva maneuver: Increases intensity of MVP; decreases intensity of innocent heart murmurs.

- Respiratory cycle: Inspiration increases blood flow to the right heart; expiration increases blood flow to the left heart.

venous hum in a child should disappear when the child is in the supine position, when light pressure is applied over the child’s jugular vein, or when the child’s head is turned.

venous hum in a child should disappear when the child is in the supine position, when light pressure is applied over the child’s jugular vein, or when the child’s head is turned.

INNOCENT MURMURS

| Murmur | Description | Proposed etiology | Common age prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Still’s murmur | Systolic Grade 1 to 2 Low frequency, such as a twanging string, musical Heard between sternal border (mid to lower position) and apex Most common murmur in children | Unknown, theories include resonant phenomena of blood movement into the aorta, or movement across a chordae tendinae | 3 to 6 years, should disappear by adolescence |

| Pulmonary ejection/flow murmur | Systolic Slightly grading in contrast to vibratory Heard over left upper sternal border, no significant radiation | Exaggeration of normal ejection vibration within the pulmonary vasculature | 5 to 14 years, most common in adolescents |

| Venous hum | Continuous, diastolic portion subtly louder Grade 1 to 2 Best heard infraclavicular and supraclavicular Only audible when patient is upright Can dissipate or exacerbate by head movements or obstruction of the ipsilateral jugular veins | Vibration of the veins carrying the blood from the head and upper body to the superior vena cava | 3 to 6 years |

Innocent vs. Pathologic Murmurs

| Innocent - Physiologic, no heart disease | Pathologic - Underlying heart disease | |

|---|---|---|

| No cardiac symptoms | Clinical | Cardiac symptoms |

| Normal investigations | Abnormal investigations: Echo, x ray | |

| Systolic | Timing | Diastolic, holosystolic, Systolic |

| Soft/vibratory | Quality | Harsh/blowing |

| Grade II or less | Intensity | Grade III or higher (possible thrill) |

| Exercise, anemia, fever Usually change with position | Louder with | Usually NO change with position |

| NO extra sounds | Other sounds | Click or opening snap, S3, S4 |

| Normal S2, physiologic split on inspiration | 2nd Heart Sound | Fixed split S2 |

- The back: Deformities, thrill, murmur

- Neck: JVP, visible pulsation and thrill, web neck, short

- Liver and spleen:

- Respiratory: Air entry, asymmetry, wheezes, basal crepitations

- Cyanosis: This is best determined by examining the patient in sunlight. Artificial light may alter patient color.

PEDIATRICS ABDOMINAL EXAMINATION

Prepared by:

*Dr. Salma Elgazzar *

WIPER

-

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

-

Introduce yourself to the parents and the child, including your name and role.

Confirm the child’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language: “Today I’d like to perform an examination of your child’s abdomen, which will involve first observing your child, then gently feeling their tummy.”

- Gain consent from the parents/carers and/or child before proceeding: “Are you happy for me to carry out the examination?”

General Appearance

-

Activity

-

Alertness

-

Abnormal position in the bed. Distressed or not

-

Appropriate size regarding weight and height for his age, just by observation.

-

Any specific medications or devices surrounding the patient.

-

Any dysmorphic features.

General Examination

HANDS

Inspect the hands for clinical signs relevant to the gastrointestinal system:

- Pallor: may suggest underlying anaemia (e.g. malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding, malnutrition)

- Peripheral oedema: associated with nephrotic syndrome (loss of albumin) and liver disease (reduced production of albumin).

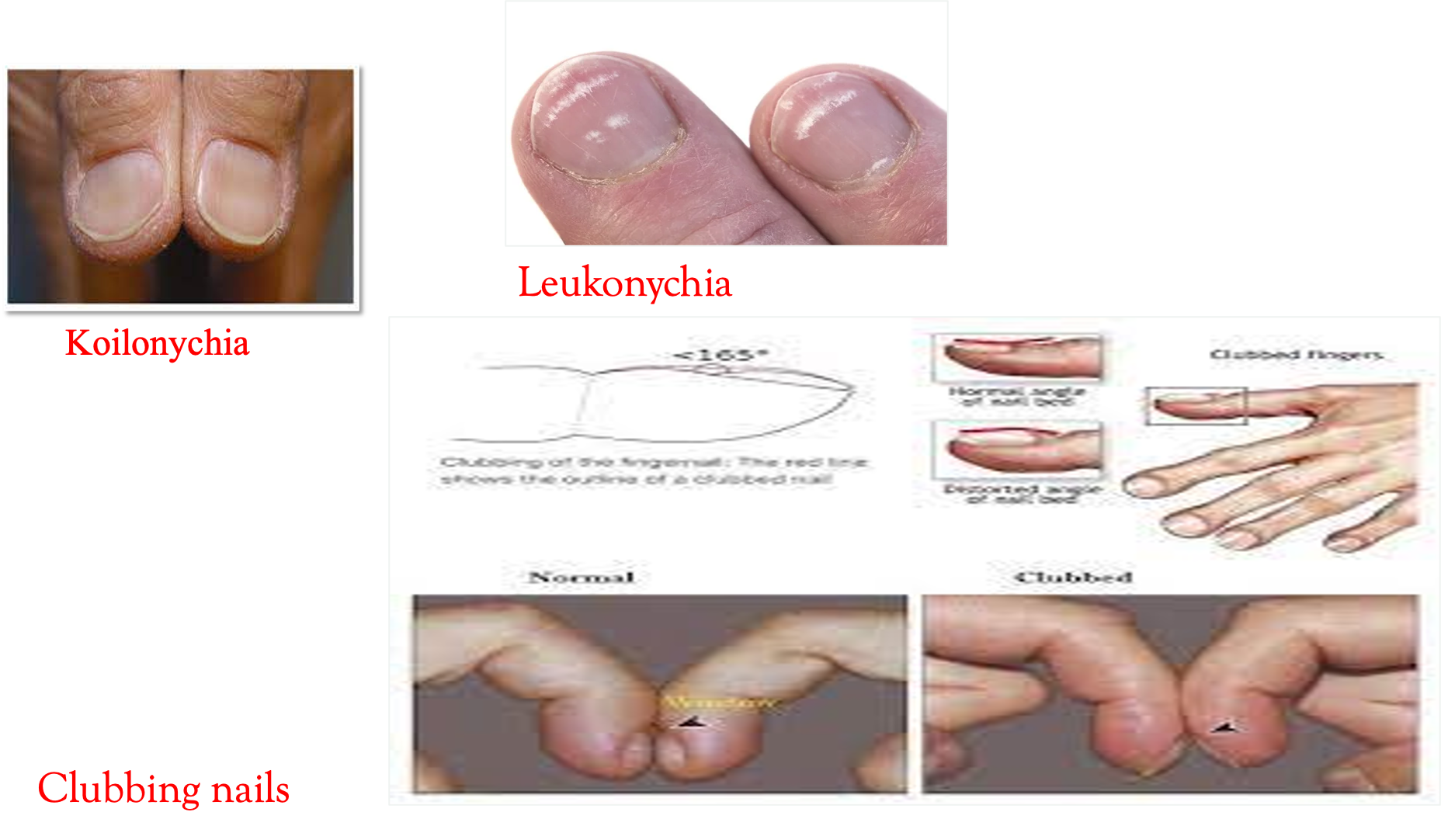

Nail Signs

- Koilonychia: spoon-shaped nails, associated with iron deficiency anaemia (e.g. malabsorption in Crohn’s disease).

- Leukonychia: whitening of the nail bed, associated with hypoalbuminaemia (e.g. nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy).

Finger Clubbing

Finger clubbing involves uniform soft tissue swelling of the terminal phalanx of a digit with subsequent loss of the normal angle between the nail and the nail bed. Finger clubbing is associated with several underlying diseases, e.g., cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease.

PULSE

Radial Pulse Palpate the child’s radial pulse, located at the radial side of the wrist, with the tips of your index and middle fingers aligned longitudinally over the course of the artery. Once you have located the radial pulse, assess the rate and rhythm. In babies, assess the femoral pulse instead.

ARM & AXILLA

- Deseferral injection pump, cannulation, etc.

- Puberty, acanthosis nigricans.

FACE & NECK

Face Observe the child’s facial complexion and features, including their eyes and mouth.

Neck

-

The left supraclavicular lymph node (known as Virchow’s node) can be one of the first clinical signs of metastatic intra-abdominal malignancy.

-

The right supraclavicular lymph node receives lymphatic drainage from the thorax and therefore lymphadenopathy in this region can be associated with metastatic oesophageal cancer (as well as malignancy from other thoracic viscera).

-

Palpate the supraclavicular fossa on each side, paying particular attention to Virchow’s node on the left for evidence of lymphadenopathy.

-

Acanthosis nigricans

Focused Examination of Abdomen

Inspection

Inspect the child’s abdomen for:

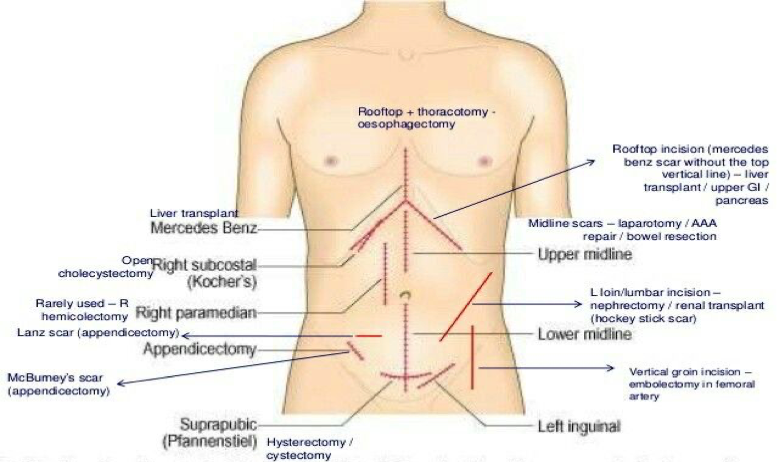

- Scars: there are many different types of abdominal scars that can provide clues as to the child’s past surgical history.

- Abdominal distension: can be caused by a wide range of pathology including constipation, Hirschsprung’s disease, ascites, organomegaly, and malignancy.

- Caput medusae: engorged paraumbilical veins associated with portal hypertension (e.g. liver cirrhosis).

- Hernias: observe for any protrusions through the abdominal wall (e.g. umbilical hernia, incisional hernia).

- Drains/tubes/stomas: gastrostomy, central venous catheter, ileostomy, and colostomy.

The abdomen is normally protuberant in toddlers and young children.

Palpation

Light Palpation

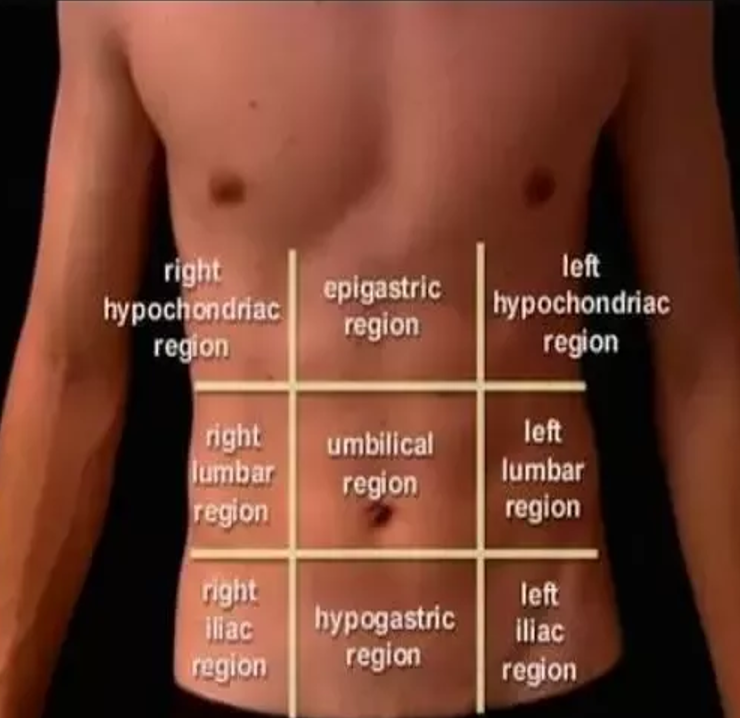

Perform anticlockwise light palpation of the nine abdominal regions, whilst looking at the child’s face and assessing for rigidity, tenderness, guarding, and palpable masses.

Guarding is suggestive of peritonitis and indicates the need for urgent surgical review.

Deep Palpation

- Localized in appendicitis (RIF), hepatitis (RUQ), and pyelonephritis (flank).

- Generalized in mesenteric adenitis and peritonitis.

Guarding: Pain on coughing, moving about/walking/bumps during a car journey suggests peritoneal irritation. A child walking, whilst being flexed forwards suggests psoas irritation (e.g. appendicitis).

Incorporating play may be used to elicit more subtle guarding:

- “Can you jump up and down?” – a child will not be able to jump on the spot if they have localized guarding.

- “Blow out your tummy as big as you can, then suck it in as far as you can” – this will elicit pain if there is peritoneal irritation.

Abnormal Masses:

- Wilm’s tumour typically presents as a renal mass which is sometimes visible and does NOT cross the midline.

- Neuroblastoma typically presents as an irregular firm mass which may cross the midline. The child is usually very unwell.

- Faecal masses are typically mobile, non-tender, indentable, and often located in the LIF.

- Intussusception typically presents with a palpable mass in the RUQ (most commonly) in the context of an acutely unwell child.

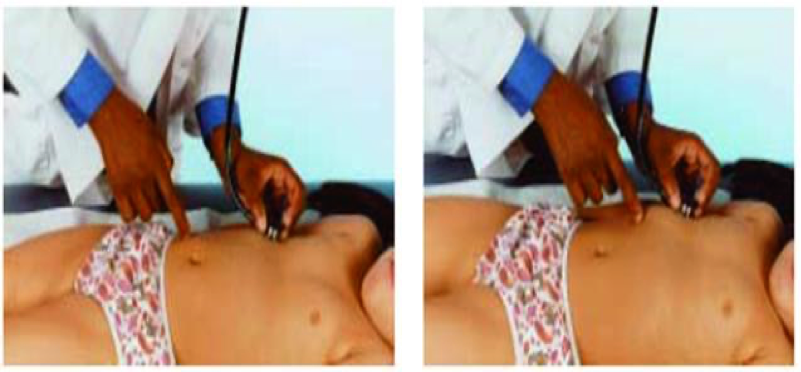

LIVER PALPATION AND PERCUSSION Palpate from the right iliac fossa and locate the edge of the liver with the tips or sides of your fingers (ask the child to take deep breaths if appropriate). The liver edge may be soft or firm and you will be unable to get above it. The edge will move with respiration. Measure in centimetres the extension of the liver edge below the costal margin in the mid-clavicular line. Percuss downwards from the right lung to exclude downward displacement due to lung hyperinflation (i.e. in bronchiolitis). Dullness to percussion can help delineate the upper and lower border. Record the span of the liver (in cm).

Tip: Young children may be more cooperative if you palpate first with their hand or by putting your hand on top of theirs.

Hepatomegaly Hepatomegaly is an enlargement of the liver beyond age-adjusted normal values. It can be due to intrinsic liver disease or associated with systemic diseases seen in infants and children.

Normal Liver Size:

- Depends on age, gender, and body size

- Average liver span is 4.5 to 5 cm (neonates), 6 to 6.5 cm (12-year-old girls), 7 to 8 cm (12-year-old boys), and up to 16 cm (adults).

Causes of hepatomegaly: There are several potential causes of hepatomegaly including:

- Infection: congenital, infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis, malaria

- Haematological: sickle cell anaemia, thalassaemia

- Malignancy: leukaemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, Wilm’s tumour, hepatoblastoma

- Metabolic: glycogen and lipid storage disorders, mucopolysaccharidoses

- Cardiovascular: heart failure

- Apparent hepatomegaly: chest hyper-expansion (e.g. bronchiolitis/asthma)

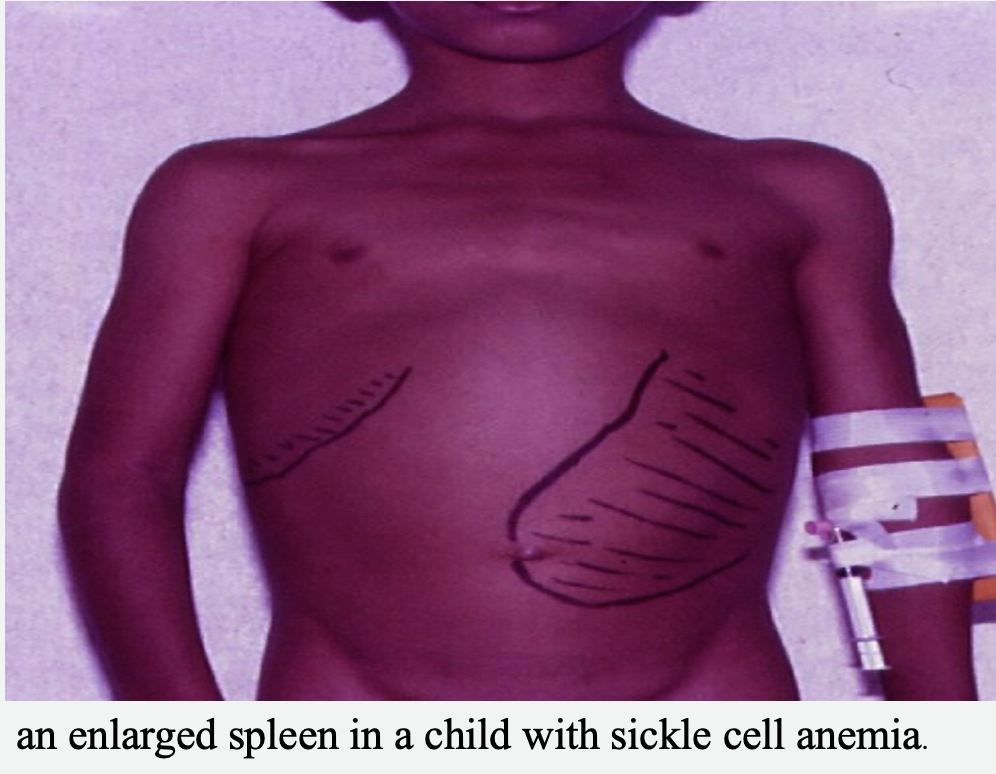

SPLENIC PALPATION AND PERCUSSION

- A palpable spleen is at least twice its normal size.

- Palpate from the right iliac fossa towards the left upper quadrant (ask the child to take deep breaths if appropriate). The edge is usually soft and you will be unable to get above it. The splenic notch is occasionally palpable if markedly enlarged. The spleen should move with respiration.

- Measure the degree of extension below the costal margin (in cm) in the mid-clavicular line.

- Percuss to delineate the lower border (splenic tissue will be dull to percussion).

Causes of splenomegaly

- There are several potential causes of splenomegaly including:

- Infection: infectious mononucleosis, malaria, leishmaniasis

- Haematological: haemolytic anaemia

- Malignancy: leukaemia, lymphoma

- Other: portal hypertension, Still’s disease

- Apparent splenomegaly: chest hyper-expansion (e.g. bronchiolitis/asthma)

KIDNEYS The kidneys are not usually palpable beyond the neonatal period unless they are enlarged or the abdominal muscles are hypotonic. Palpate the kidneys by balloting bi-manually in each hypochondrium. You can ‘get above them’ (unlike the spleen or liver) and tenderness implies inflammation.

Causes of Kidney Enlargement:

- Unilaterally enlarged: hydronephrosis, cyst, tumour

- Bilaterally enlarged: hydronephrosis, kidney stones, polycystic kidneys

Percussion

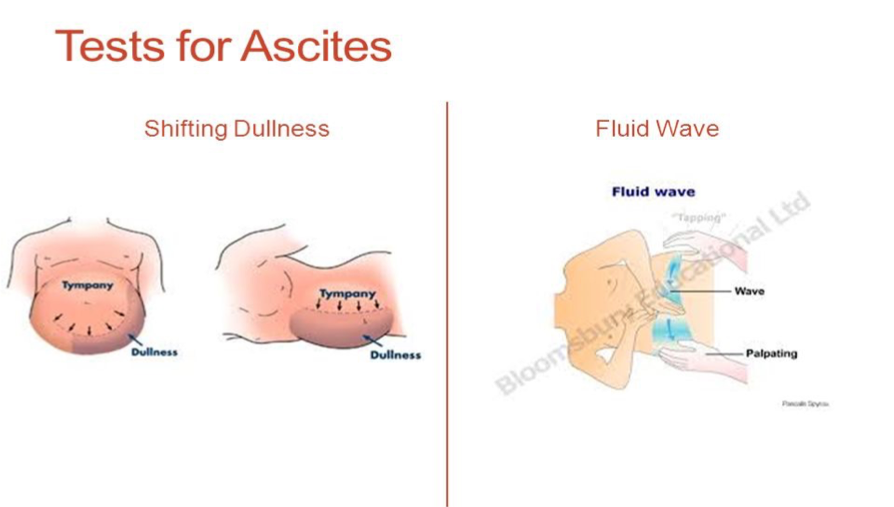

ASCITES Ascites may be present in cirrhosis, hypoalbuminaemia, infection, or malignancy. The presence of shifting dullness is highly suggestive of ascites.

Assessing for Shifting Dullness

It is usually not possible to formally assess for shifting dullness in young children, due to issues with co-operation. However, in older children, it may be possible.

- Percuss from the umbilical region to the child’s left flank. If dullness is noted, this may suggest the presence of ascitic fluid in the flank.

- Whilst keeping your fingers over the area at which the percussion note became dull, ask the child to roll onto their right side (towards you for stability).

- Keep the child on their right side for 30 seconds and then repeat percussion over the same area.

- If ascites is present, the area that was previously dull should now be resonant (i.e. the dullness has shifted).

Auscultation

Complete examination with

-

GENITAL EXAMINATION

-

RECTAL EXAMINATION

Not routinely performed and if indicated, it should be performed by a specialist who has experience interpreting findings. The rectum may be inspected to identify relevant abnormalities:

-

Imperforate anus

-

Anal skin tags (Crohn’s)

-

Anal prolapse

-

Staining of underwear (may suggest constipation)

-

LOWER LIMB